To the Faith Community Regarding Brittany Maynard

I’ve been seeing status updates like the one below floating around social media by those claiming to be apart of the religious community.

As someone who considers himself a part of the faith community, I’m going to hope that this type of rhetoric represents a fringe opinion of a small segment of the faith community that (unfortunately) would rather extend judgment than grace and is more satisfied in self-righteousness than empathy and compassion. And while I’d be presumptuous to assume that the majority within the faith community AGREE with Brittany’s decision, I AM going to assume that the majority of the faith community have NOT looked upon Brittany Maynard and deemed her a “coward”. My hope is that the majority have attempted to understand her situation and have embraced the tension that “death with dignity” may place upon your faith system.

As someone who considers himself a part of the faith community, I’m going to hope that this type of rhetoric represents a fringe opinion of a small segment of the faith community that (unfortunately) would rather extend judgment than grace and is more satisfied in self-righteousness than empathy and compassion. And while I’d be presumptuous to assume that the majority within the faith community AGREE with Brittany’s decision, I AM going to assume that the majority of the faith community have NOT looked upon Brittany Maynard and deemed her a “coward”. My hope is that the majority have attempted to understand her situation and have embraced the tension that “death with dignity” may place upon your faith system.

I know the tension. We want to respect the traditions of our faith and the held certainties of our scripture and yet we also — to some degree or another — want to extend compassion, understanding and mercy. This is the tension of the faith community: we have one foot planted in tradition and another foot planted in the present.

Is Choosing “Death with Dignity” Actually Suicide?

Monsignor Ignacio Carrasco de Paula, a Vatican official and head of the Pontifical Academy for Life condemned the death of Maynard, calling her death “an absurdity.”

“This woman [took her own life] thinking she would die with dignity, but this is the error ….

Suicide is not a good thing. It is a bad thing because it is saying no to life and to everything it means with respect to our mission in the world and towards those around us …

Brittany Maynard’s gesture is in itself to be condemned, but what happened in her conscience is not for us to know.”

The assumption that Brittany Maynard and those who would choose “Death with Dignity” are committing suicide and saying “no to life” isn’t as bullet proof as we’d like to think. It’s important to remember that — by law — those who choose “death with dignity” (such as Maynard) must have two medical doctors confirm that the patient is indeed terminal and will die within six months.

Unlike suicide, the terminal patient isn’t making a choice between death and life, it’s a choice between two kinds of death. Ethan Remmel PH.D wrote about his terminal illness for Psychology Today back in 2011. He writes:

“I have received some feedback on my thoughts about the Death with Dignity Act. As I said, I have not decided whether to use this option, but I feel strongly that it should be legally available to mentally competent and terminally ill people such as myself. As I also said, I do not view it as “suicide” (although that is a convenient term), because I would not really be choosing between living and dying. I would be choosing between different ways of dying. If someone wishes to deny me that choice, it sounds to me like they are saying: I am willing to risk that your death will not be slow and painful. Well, thanks a lot, that’s brave of you.”

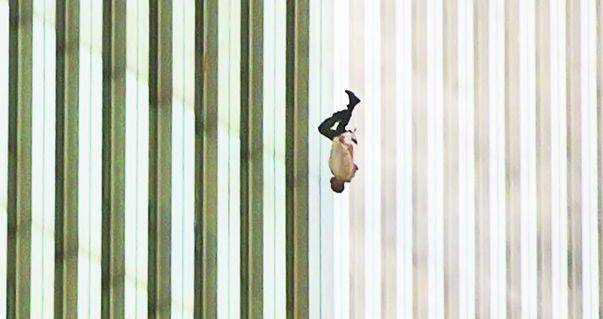

Perhaps Richard Drew’s “The Falling Man”, a picture of a man who jumped from the World Trade Center on 9/11 drives home Remmel’s point:

Is “The God Argument” Really Helpful?

Another element – and a VERY strong element – is the belief that God and ONLY God should choose when a person dies.

I can understand the passion that resides in the hearts of believers. And while the God element is the center of the believer’s life — we need to understand that – on a national and state level — this discussion is not being held in a church forum, it’s being held in a public sphere. And so the “let God decide when we die” arguments wouldn’t work outside the walls of our houses of worship. If you are a believer and you disagree with “death with dignity”, it’s certainly okay to voice your opinion — in fact you should — but realize this America isn’t the America of a couple decades ago and “the God argument” won’t suffice.

Furthermore, the conversation is simply too complex for the “let God decide when we die” answer. With modern technology, the situation is often the case that humans do indeed have some say in the matter. Whether it be passive euthanasia, like taking off life support and forms of palliative care (i.e. hospice), we often have to make the decision whether or not to continue to pursue medical support.

In fact, now more than any other time in human history, humans are presented with this choice: Do we want quality of life or quantity of life? Do we want to extend life through artificial means, or do we forego medical aid and die on our own terms? We are being asked to make decisions that were previously “left up to God.” We are, as we grow and expand our knowledge of the human body, determining more and more of our fate. And as medicine has created “miracle” after “miracle” there has to be a point when we say, “I’m tired of the miracles. I’m ready to die.”

When the Faith Community Embraces End-of-Life Care

When community is at the center of death, the end stage of life becomes not an embarrassment of dependence, but a beautiful display of love … a time when the community shines forth its compassion, care and giving. When you have good community and you’re terminal, there are few things that display the beauty of community more than the end stage of life.

I‘ve seen it and let me say that while death is always somehow painful (even for those who choose “death with dignity”), it’s not always ugly. There’s few things that move me more than seeing the loving care of a family who have utterly surrounded their loved one in both the dying and in the death.

So here’s my main point: the “good death” isn’t ultimately defined by one’s lack of pain, but by one’s family and friends … or by one’s faith community. The good, terminal sickness is defined by having family over 24/7, sharing the experience, sharing your words of love through actions.

And actions — our orthopraxy — is where the faith community has something to say in the end-of-life discussion. In a time when we major on apologetics and words of orthodoxy, it’s important to remember that “I was sick and you looked after me” is the call of believers. When the aged are becoming the marginalized of society, being sent away to nursing homes and retirement communities where they can be hidden from the rest of us; when the sick are sent to cold, sterile hospitals; it does us well to remember that whether or not we agree with Brittany’s decision, it’s our mandate to speak words with our actions by providing love, gifts and — perhaps most importantly — community for the sick and dying.

This entry was posted by Caleb Wilde on November 7, 2014 at 8:59 pm, and is filed under Community, Dying Well, Euthanasia, Orthopraxy. Follow any responses to this post through RSS 2.0.You can leave a response or trackback from your own site.