World Vision Uganda

10 Things You Need to Know about Child Sacrifice in Uganda

Full disclosure: I traveled to Uganda under the auspices of World Vision (a Christian humanitarian aid, development, and advocacy organization) to write about the programs World Vision is implementing in Uganda, including their efforts to fight ritual child sacrifice. They invited me because they thought I might be able to process and compose some thoughts on Uganda’s darker stories.

One. It’s Happening. Actually, Literally Happening.

Before I flew to Uganda, I was skeptical that something like “ritual child sacrifice” was taking place in the 21st Century. I was especially skeptical that the term “child sacrifice” was exactly what it sounds like. Just like politics, charitable organizations can oversimplify and slightly exaggerate tragedies to garner emotions, empathy and hopefully support, especially support of the financial kind (anyone remember that Sarah Mclachlan ASPCA commercial?).

After spending a week in Uganda and listening to a Mother tell the story of her child’s abduction and eventual rescue, seeing a localized Amber Alert System, and seeing the palpable fear in the local communities, I can say that this isn’t a simple story, but I do feel like I can represent some of the things that are happening.

Specifically, I can say it’s literally happening. Ritual child sacrifice is happening in Uganda. In fact, the week I was there, two children were abducted and murdered as a ritual sacrifice in two separate districts.

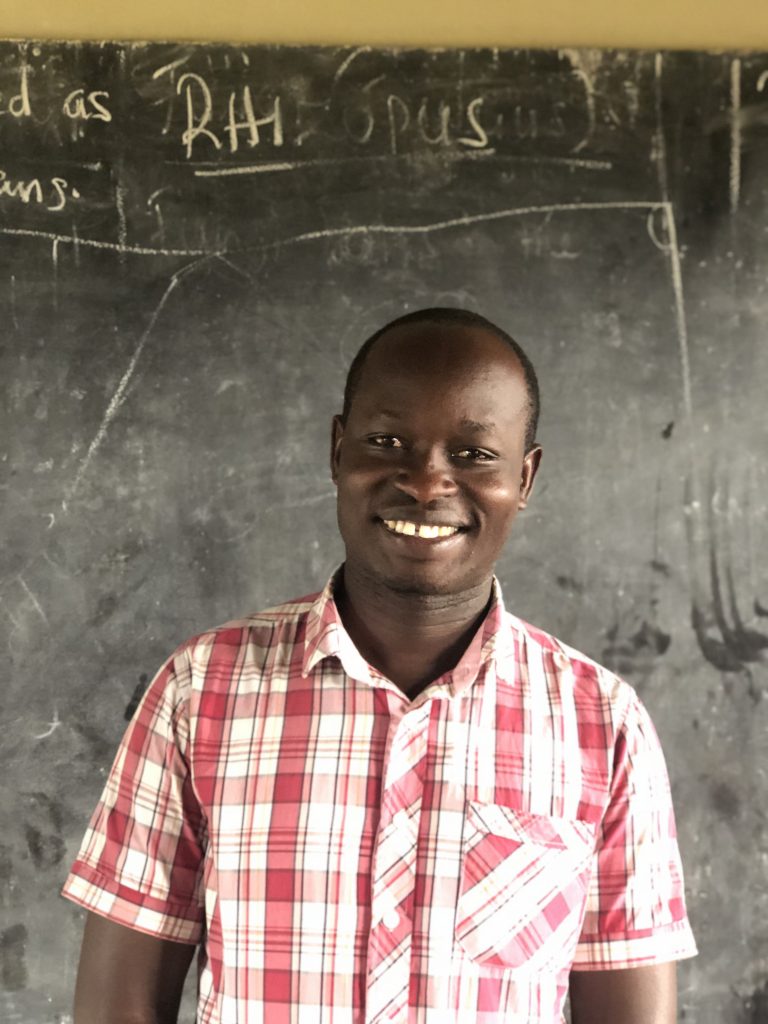

Two. Stopping Ritual Child Sacrifice is this Man’s Life Work

The first time Obed — the World Vision director spearheading efforts in Uganda to stop child sacrifice — saw a child sacrifice victim, he was teaching a World Vision child protection course in a country tribe. He heard some screams, ran to the location the screams were coming from and found a mother hysterically yelling over the decapitated body of her 8-year-old son. The murder had happened only moments before she found him. Obed, in a frenzy, scooped up the body, jumped on a moped and started driving to the nearest medical clinic, “because,” he told me, “the boy was still moving and I thought I could save him. Of course, I was traumatized, and still am” he confessed.

By the time Obed returned to the village, the suspected murderer had been killed by a mob of angry tribesman. Obed showed me photos of both the murdered boy and the murderer. From that point on, Obed hasn’t stopped working to protect children AND working with local authorities to establish laws and protocol that help convict the murderers while moderating mob justice.

Three. It’s Like the Moral Panic of a Serial Killer

Here’s an example of moral panic: In 2002, the Washington D.C. Sniper Attacks were picking off drivers on I-95. During three weeks, the snipers killed 10 people. Only 10 were killed out of the hundreds of thousands of people and cars that passed through the Beltway. I was one of those travelers (driving a veteran to Arlington Cemetery for burial). I was a little frightened … even though — based on percentages — it was much more likely I’d be killed in a car accident than by a sniper shot.

Likewise, known serial killers only murder a minuscule percentage of the population, but they can put fear in the hearts of an entire region when they’re actively killing. Ritual child sacrifice in Uganda is the same, except it’s not a person that’s behind the murders, it’s a complex system of beliefs and societal ills.

Four. There are two kinds of child sacrifice in Uganda.

The most popular of the two involves abduction, murder, and the removal of certain body parts, including blood. Those parts are taken to the witchdoctor who uses them for remedies and spells.

The other form is usually committed by family members of the child, so it’s much less publicised. This form of child sacrifice takes place when a family sets aside one of their children (or an abducted child) as a sacrifice for the spirits to feed on. The child is routinely drained of blood. Many of these children eventually die or suffer severe impairments.

Five. The Ritual Stems from Ugandan’s Belief in Witchcraft.

Witches (a gender-neutral term) and witch doctors (again, gender neutral) are two different things, but both dabble in witchcraft. Witches can cast evil spells (some Ugandan’s believe AIDS is caused by the spells of witches and evil spirits), while witch doctors are “traditional healers”, they create remedies to heal the effects of evil witchcraft and evil spirits (many believe that witch doctors can heal AIDS). It’s estimated that there are three million “traditional healers” (witch doctors) in Uganda.

Obed explained that Ugandans believes there’s witchcraft power in the shedding of blood. Usually, that blood is shed from animals sacrificed at local shrines. But as people have become more desperate to manipulate and appease the spirits, they’re now turning to the shedding of human blood and other human body parts.

When Obed talked about Ugandan witchcraft, it wasn’t the way I’d talk about it. I talk about witchcraft like it’s some superstitious mental manipulation that preys on people’s fears. But, and this is a big “but” … I don’t believe it has any actual supernatural power. Obed — a college educated Ugandan who’s married to a lawyer — believes differently. He’s seen it work, he says. He’s seen supernatural power. And I think the whole country feels just like him. Nearly all believe that physical problems are the result of an unseen, supernatural world.

Six. Why human blood?

Some witchdoctors believe that the shedding of human blood guarantees wealth and success, or the immediate lifting of a curse for the one making the sacrifice.

Seven. Why children?

They’re vulnerable, easy targets that can be abducted and killed with more ease than an adult.

Eight. How It’s Done.

This from Obed’s little track on child sacrifice:

Child Ritual Murder is one of the most extreme manifestations of violence against children in Uganda. This gruesome practice involves mutilation and removal of children’s body parts and blood while the child is still alive for wealth.

Obed told me that the head is the most prized body part, which is usually severed with a machete. The remaining parts of the child are often left exactly where the child was murdered … in a field, or along the side of the road. Sometimes the child is captured and brought to a witch doctor, who performs the sacrifice. Other times, only internal organs are taken while the child is still alive.

Nine. Child Sacrifice Is a Symptomatic Problem

In Uganda, when a family is in extreme poverty, they’ll often sell their girls to older men for marriage starting at eight years of age. Because they’re so young, many will get pregnant as soon as their bodies are able, and either their babies or they themselves die from the physical labor of a pregnancy at such an early age.

And because polygamy is legal in Uganda, many of these young women are forced to raise and provide for their children on their own while the men attend to their own wants and needs and other families.

Many girls are sexually abused at a young age.

Most children are physically abused at a young age.

Uganda sometimes experiences famine.

There’s corruption on every level in politics (YouTube has some fun videos of physical fights in the Ugandan parliament).

THERE ARE SO MANY THINGS THAT CONTRIBUTE TO THIS PROBLEM.

And when this confluence of problems hits a family, or a community, the extreme poverty coupled with Ugandan witchcraft results in some people taking extreme measures, like child sacrifice.

Child sacrifice is a problem, but its a symptom of a complex confluence of more prevalent problems.

Ten. What Obed and World Vision Are Doing.

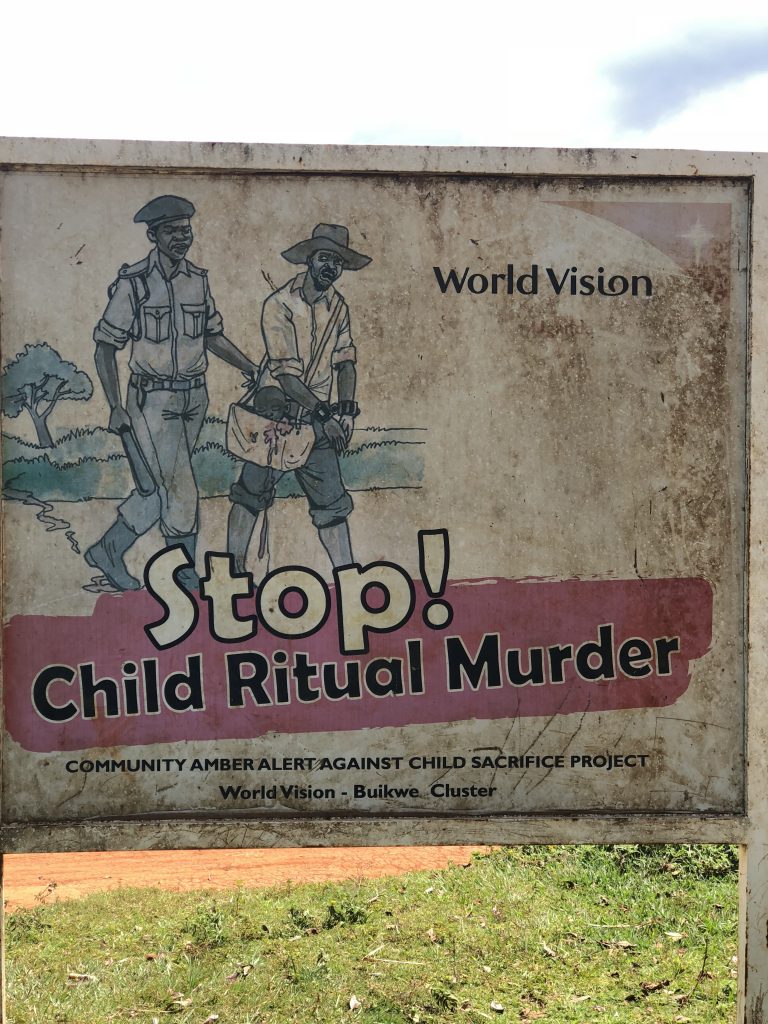

Obed and World Vision are spearheading efforts to stop child sacrifice through an integrative approach that involves a localized Amber Alert system for child abduction, connection and outreach to Uganda’s network of shaman and witch doctors (challenging the beliefs that call for child sacrifice), the Ugandan law enforcement and government (to create and enforce more thorough child protection laws) and community educational programs that work at a grassroots level to elevate the awareness of child abuse on all levels, from the home to the school.

This work consumes Obed. His sleep is interrupted by the screams he’s heard. The images he’s seen constantly flash through his mind. And he’s often very lonely in his efforts. The last day I was in Uganda, we talked for two and a half hours about everything from the times he’s held dying children, to the victories he’s had, and the complex belief system and motivations that cause a person to sacrifice a child.

He showed me the files he keeps on each child sacrificed. He told me their stories. Showed me their pictures when they were both alive and dead. He keeps extensive notes for each case. Notes that detail everything from what parts were taken from the child, the suspected murderers in each case, the current legal proceedings, and the efforts he’s put forth in counseling and supporting each child’s family.

- Obed (and other World Vision staff) teach extensive programs in the communities that “promote change of harmful beliefs, norms and attitudes causing violence to children.”

- Obed is building relationships with witchdoctors, as well as working with both Christian and Muslim religious leaders to promote child protection.

- He’s advocated and succeeded in passing by-laws and ordinances for child protection.

Since Obed and World Vision have focused their efforts on the Buikwe District (called “The Capital of Child Sacrifice”):

- A total of eight children have been saved through the World Vision lead amber alert system (the tribes use a specific drum beat to alert the community).

- Child rape has been reduced from 306 cases in 2012 to 126 in 2017.

- In 2017, child sacrifice was down 74% compared to 2015.

- Child marriage has been reduced from 44.4% in 2015 to 38% in 2017.

- World Vision’s Child Protection Clubs are empowering students to know their rights (I sat in on one such club and it was wonderful).

I believe in Obed. I saw enough of him, enough of his notes, enough of his work to believe that all these stats aren’t the kind of fluff stats organizations put out to garner support.

It’s been a week now since I left Uganda. I’ve been telling people that Uganda is NOT Las Vegas. What happens in Uganda comes home with you. It stays in you. It’s a beautiful country, with beautiful traditions, and beautiful people. Uganda doesn’t equal child sacrifice. This doesn’t define them.

But, it is happening. It’s happening because there’s a devaluation of children, especially girls. It’s happening because child marriage and polygamy are keeping women out of school. It’s happening for so many reasons.

Money won’t solve the problems in Uganda, but it can help people like Obed and the children he seeks to protect.

*****

If you want to support World Vision’s work in Uganda, click HERE.

Sometimes the World Needs More Feminism, Not More Jesus

I finished writing this post at 1:30 AM EAT after a 12 hour day of traveling the Ugandan countryside listening to some intense stories. The long day, the jet lag, and the emotions of this whole experience created this post … something that’s slightly more passionate in tone than my normal style. It’s 6 AM right now, I just woke up and reread it before we hit the road again, and a part of me wants to redact the tone, and the other part (the part that’s winning out) wants to let the post live on its own. So, I’ll let it live, albiet with this preface letting you know it was written “in the moment”:

All the photos in this blog post are credited to Laura Reinhardt.

You’re probably here for one of two reasons: you’re offended, or you’re intrigued to see how Caleb’s going to pull this blog post off without causing a holy war.

Let’s get right to it.

I’m in Uganda right now doing what I’m calling “social awareness tourism.” I’m not here as a missionary or a humanitarian, I’m here to listen and write about whatever it is the Ugandans and World Vision – the people and program that is sponsoring this trip – want to tell me. I did know before I came here that we’d hear about child sacrifice practices and the Ugandan people who are working to end it; and we’d hear about the Ugandan people and programs that help vulnerable children, especially the most vulnerable population of Uganda: girls.

I came here to Uganda expecting to hear and retell the stories about the child sacrifices that are going on through Witchdoctors and Shaman, the Amber Alert System World Vision has implemented into local villages to stop abductions, and the retelling of the heart-wrenching story from a survivor of child sacrifice. I thought, “That story fits my death brand, so that will be my thing to write about since the rest of the writers on this trip are women and will likely pick up on the wonderful things World Vision is doing for vulnerable children, especially vulnerable girls. I’ll write about child sacrifice BECAUSE THAT’S IMPORTANT TO ME, and they’ll probably want to write about the girls BECAUSE THAT’S IMPORTANT TO THEM.

I was right and wrong. I will be writing about child sacrifice, and the lovely lady writers of this group will likely be writing about World Vision’s involvement with at-risk girls (and they’ll probably be writing about the movement to stop child sacrifices).

A young Ugandan girl telling us how she aspires to be the chief of Ugandan’s law enforcement so that she can help protect the vulnerable, especially the girls.

I realized how I was wrong … when yesterday and today happened.

Yesterday, it was explained to us how the simple fact that Ugandan girls don’t have access to sanitary items — like pads — they’ll often miss school for the duration of their periods. That they’ll sometimes miss enough school – if they’re periods are heavy and long – that they’ll drop out of school completely because they’ve missed too much school time. BECAUSE THEY LACK ACCESS TO PADS!!!

A couple of girls and boys (!!!) from a World Vision sponsored program demonstrated to us how they make reusable and sustainable pads for the young girls in the surrounding area. World Vision explained how this program is replicating itself throughout Uganda, keeping girls in school.

Today, it was made much clearer WHY having the girls stay in school is so important. Sara, a Ugandan native and the director of the World Vision Uganda program called SAGE (Strengthening Community Accountability for Girls’ Education) said it this way, “Education is the cure to societal ills.” I know what you might be thinking … maybe something like, “well that’s a liberal agenda.” And yes, it might be. But here, it’s less an agenda, and it’s more a reality.

This is Sara, the director of the SAGE program.

In Uganda, when a family is in extreme poverty, they’ll often trade their girls to marry men. The men trade back a decent supply of food or other items that can increase the family’s food supply and decrease the family’s suffering. Before we judge, imagine you had five children and you couldn’t feed any of them unless you sold one to feed the four. It’s horrible, it’s sad. Let’s pray none of us ever are put in a situation where we have to make such a decision.

The girls are sold off to men starting at eight years of age. Because they’re so young, most will get pregnant as soon as their bodies are able, and often either their babies or they themselves die from the physical labor of a pregnancy at such an early age.

Once they’re sold into marriage, they won’t complete their education; they’ll have babies – sometimes beginning at the age of 13 through 14 – and they’ll be forced to raise the children (because that’s what the women in Uganda are supposed to do) as young teenagers.

The other way poverty can breed poverty is that young girls will be asked to quit their education to join the workforce and help the family’s financial situation. A lack of education means less opportunity for a professional occupation, which means less opportunity for a living wage.

How was I wrong about what’s important for me to write about here in Uganda? I WAS WRONG TO BELIEVE THAT THE VULNERABILITY OF THE UGANDAN GIRLS WASN’T IMPORTANT TO ME … THAT THIS TOPIC IS JUST FOR THE FEMALE WRITERS IN OUR GROUP TO ADDRESS.

If the girls of Uganda can learn their value, if they have structures in place in their school and in their community to help them through the prospects of being forced out of school by poverty or marriage or labor; when the girls have access to sustainable sanitary care; when the girls are empowered to dream big, when they can effect change, they can lead a country out of its social ills. And this affects me in every way possible.

How do I know?

At the end of the day today, Sara showed us one of the groups of Uganda girls in her SAGE program. The girls told us of how they’ve learned their value through Sara’s mentorship, and how the girls hold the other girls in the school accountable for staying in school. If one of their classmate’s attendance starts to fade, these girls from SAGE reach out to that classmate, ask them what’s wrong, ask them what they need, and then the SAGE girls contact the school superiors to intervene. The superiors listen and do everything in their power to make sure that girl continues her education.

The elected student leader of the SAGE program.

The rest of the young girls we met over the last two days were usually asked to introduce themselves to us (we were asked to do the same thing for them). Most girls would speak in such a small, quiet, shy, abashed voice that we couldn’t hear them. Even when they were prompted to speak up, they didn’t … or they couldn’t. Because they’ve been ingrained by a societal belief that men are their superiors. And that’s the crux of this whole thing: the men too often treat the girls and women poorly because the men believe they’re superior (and let’s not be so cocky to think this is just a problem for Ugandan men).

The SAGE girls didn’t speak in quiet voices. They spoke loud, eloquently, and confidently. They told us how they wanted to become teachers, social workers, doctors, lawyers, and government leaders. They told us how they wanted to fight for the rights of the most vulnerable. How they’d pursue an education that could give them professions with platforms to make a change for the girls of Uganda.

After listening to these girls talk, Sara opened up a time for us to ask the SAGE girls some questions. I interjected, “I don’t have a question for you, I have something to say”

I told them we – the men – need them.

I told them that men hold all the power positions.

I told them that as they rise up, that nobody likes to give away power, especially men. That they’ll be told, “no” time and time again, but that they’ll need to say, “yes” to ever “no” they’re told until they see their dream made real.

Because it’s not only men that need them, the world needs them.

We need their voice in all the conversations that have been dominated by men.

That they’re strong. That their voice matters. That I’m waiting in anticipation to see what they’ll accomplish, to hear their voice, and learn from all they have to give.

“According to the national census of 2014, Christians of all denominations comprised 85 percent of Uganda’s population.” Jesus has already arrived here. He’s been here over a hundred years ago when the church in all it’s various forms and denominations started to arrive. And while Jesus plants the seed of equality (because “God so loved the world”), what has to grow right now is the belief that a woman is just a valuable as a man; that every woman has a right to education; every woman has a right to choose their spouses; every woman has the right to pursue her dreams, and every woman has the right to equal professions with equal pay. That’s feminism.

Feminism isn’t a woman’s agenda.

It’s our agenda.

It’s my agenda.

Jesus has already arrived. And Jesus has done good for this country. When Christianity first came to Uganda, Christianity had a large part to play in squashing the beliefs behind child sacrifice, and destroying it completely until the practice was revived a couple of years ago.

This country – and me and you — will be saved from many of our current ills when the girls arrive.

*****

If you’re interested in supporting World Vision’s people and programs in Uganda, click HERE.

To my 19-year-old self: I want to let you know, I’ve become a failure

The guy on the right is me (for clarification). Also for clarification, this guy isn’t a witch doctor. He’s a dancer for the Ndere Cultural Centre.

A PREFACE: I’m in Uganda with World Vision for the next week doing what might be called “social awareness tourism” (I’ll be writing about what I’m doing for the next week, which might get so boring you’ll be begging me to talk about dead people again. Actually, it won’t be boring. I’m here to tell the stories of the locals who are fighting against child sacrifice. The last time I was in Africa was when I was a 19-year-old missionary trekking medical supplies to indigenous villages and handing out Bibles to people groups that had never been introduced to Christianity. Being back on this continent has brought back memories of my 19-year-old self, and I feel the need to explain to him why I’ve failed him. This is a vulnerable piece, so be nice to me.

To my 19-year-old self,

Let’s get this out of the way. I’m not the person you wanted to become. I’m the person you fought so hard to avoid. I know that you’re a stoic idealist (even though I don’t think we realized it at that age), and I know that you like truth (that part hasn’t changed), so I’m gonna get the hardest part out of the way, and this is going to upset you, but here it goes: You aren’t a missionary, or a humanitarian worker, or a pastor.

You work at the funeral home. It’s a tough job that’s taken a lot out of you. You’ve stayed because you’re able to hear the pain of those you work for and lift them up without diminishing their grief. You think about quitting your job at least once a week, but the hard and difficult stories you see have unleashed a part of you that feels at home in the dark spaces.

Here’s the other part that’s going to be tough to swallow: you don’t go to church any longer. I want you to know there’s a good reason you don’t go. And you should also know that I’ll go back if I’m ready, although it likely won’t be to a church you’d approve. I’m more comfortable with silence now. I’m okay with not having answers to all the questions. I found that God’s children are all over the place. And as much as I want to explain all that, as the great poet once said, “It’s the climb. Yeah ea, yeah ea!”

There are some other small things you probably wouldn’t like: you curse, you let your shoe fetish get the better of you, your hairline is receding and – this probably won’t come as a surprise because you ALWAYS questioned this part of your upbringing – you are an ally to the LGBTQ community. Oh, and those six-pack abs never came in, and you’re still not entirely comfortable in your skin.

BUT, that girl you have a crush on? You married her. And that book you were working on? That 150,000-word book? That one sucked. The one you did get published isn’t a best seller, but it won an award. You have an absolutely beautiful son and you’re a damn good father.

I’m writing all this because I am here in Africa again, and I thought I’d let you know so you can be just a little proud of what I’ve become. I’m not here as a missionary, I’m here as a writer. I’m not telling my truth, or the story I think I should be telling them. I’m here to witness them, not witness to them. I’m here to listen and tell their story

I’m sorry we didn’t turn out the way we anticipated. Keep going, forgive yourself, believe that God loves you (there’s going to be a decade where you won’t), and smile more, because your story hasn’t followed the path you’d hoped, I think you’ll find it’s ended up someplace even better.