Death of a Grandparent

To Bury a Father

This post is by photographer KIMMO METSÄRANTA. It is used with Kimmo’s expressed permission.

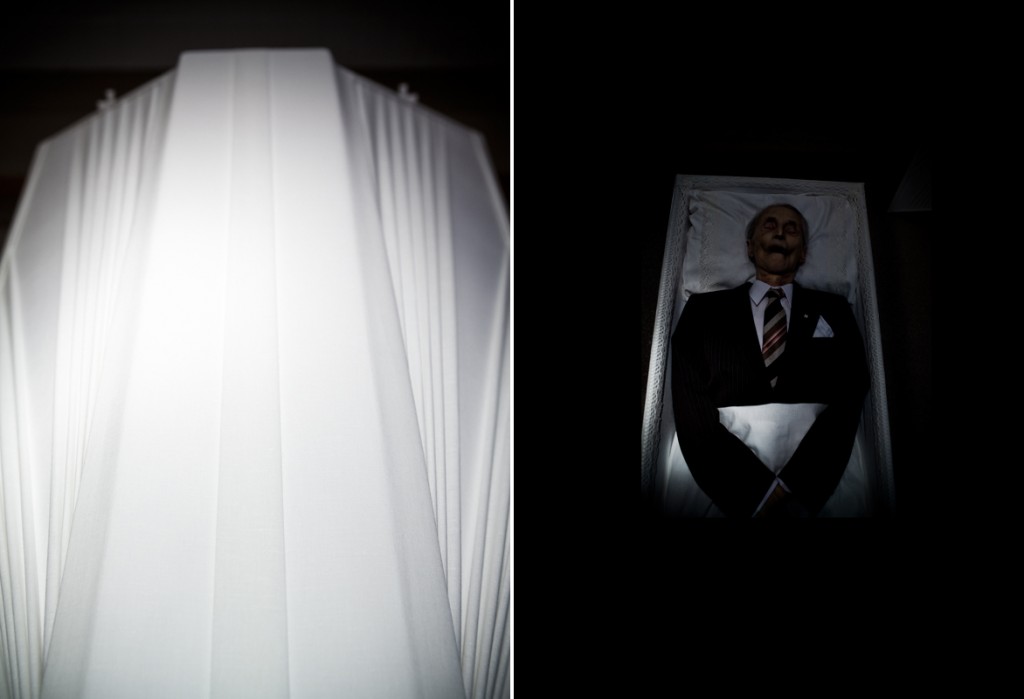

My grandfather died in the spring of 2014. It didn’t come as a surprise to anyone. During the last two years he didn’t respond a lot, he wasn’t present. I don’t know if he thought about dying, was he expecting it, afraid of it. I don’t think so. He was 87 years when he died.

My sister and I prepared him for his coffin with the mortician. We dressed him into his best suit, combed his hair. It felt like a last favour for him. Maybe I was trying to compensate the fact that I visited him far too seldom. I don’t have a clear conscience about that.

Most people in Finland don’t know that you can go dress the deceased. And if they did they probably wouldn’t do it. Death is still a taboo. You are not supposed to talk about it, little alone to show pictures about it. I don’t know why this is. Maybe we don’t want to be reminded of the fact that none of us is immortal.

My grandfather and I were not close for many years due to the fact that he and my grandmother lived far away. Only after he ́s condition started to deteriorate did I make more effort to visit them. The visits were not easy. He didn’t have his hearing anymore and my grandmother had no short term memory. She would ask the same questions again and again and he would sit in the table and smile, not knowing what we were talking about. But he seemed pleased that he still recognised me.

The moment of preparing my grandfather was beautiful. Time seemed to come to a halt. There was no hurry, nothing outside the present moment. All the memories felt stronger, more concrete. During the years I had photographer him on many occasions, he always had this amazing feeling of presence. This was our last shoot together although in some sense he was no longer here. Merely a shell was left. I took photos for a few minutes, then I closed the coffin with the mortician. That was that. The last time I saw him.

Later as I watch the pictures he seems to be at ease. And there still is that sense of presence. In some way I feel a lot closer to him now than I did before.

2014

back to work

You can see more of Kimmo’s work HERE.

Death and Funerals

Today’s guest post is written by Laura Bock.

“Each of us has his own rhythm of suffering.”

– Roland Barthes

Death and funerals have never frightened me; I’ve had my share of close encounters with death, mostly from my own period of suicidal thoughts due to severe depression. Death and I have become friends of sorts over the years.

I’ve always held a fascination with death, even as a child. With my fascination came an understanding; I accepted death as a natural part of life at an early age. I knew all living things had to die; from the moment of birth, we are essentially living to die.

My mother didn’t want me attending funerals when I was young; she did not fare well with funerals and did her best to never attend any. I am thankful I didn’t pick up on her phobia.

When I was around 12 years old, I experienced the death of two major people in my life: my Nana and the pastor of the church I was attending.

My Nana’s death was sudden, yet expected; she had emphysema and was in the ICU when she passed on. I remember going to see her in the hospital with my nephews, who were just toddlers; we had to slip in quietly, because we were so young and it was after hours. Nana took my hand, squeezed it and told me not to be sad; I had to be strong for my dad and the rest of the family.

I was sad, but even at that young age, I knew to not dwell on her passing, but to rejoice and celebrate her life by remembering how she touched my life and the lives of others.

At her funeral I bounced around smiling, singing and laughing, trying to make everyone smile. My dad held my hand and took me up to Nana’s casket to say goodbye; I touched her hands placed peacefully across her torso, with her rosary in hand, then looked up and smiled at my dad who was holding back his tears. “Don’t cry dad, she’s at peace and doesn’t want you to be unhappy.”

After returning home from Nana’s funeral, I went through my grieving process. The hardest part was accepting the fact that when we would go to visit her house, that she wouldn’t be there anymore. The first time we visited after her death, I stood in the spot where her rocking chair was, right in front of the window looking out to the road; I pretended she was still there. I could feel her presence; I knew she was watching over all of us.

It seemed like hardly any time passed when the pastor of my church suddenly died. He was working on a car in his driveway when the jack gave out and the car crushed him underneath. This death was more shocking to me than my Nana’s.

When I attended the pastor’s funeral service, my philosophy on death was reinforced by the happy and uplifting hymns that were chosen for the service. I knew that life had to carry on, and while we would always miss the person we lost to death, we should always remember to celebrate their life. I became a pro with funerals at a young age.

I remember collecting all the loose change I could, putting it into an envelope and giving it to the pastor’s widowed wife with a letter that said what he meant to me and how sorry I was for her and her sons’ loss. I ran into her about 10 years ago; she still remembered my act of kindness.

Immediately after graduating high school, a friend of mine was killed in a car accident; she was very popular and the wake was packed wall to wall with friends and loved ones. Everyone was crying – except me. I remember being told by a close friend that I was insensitive because I was not upset and crying like everyone else was. My reply was simple, “Everyone mourns death in their own way. She is at peace – we should celebrate her life.” I understood I was merely a target for her anger as part of her grieving process.

I make it a habit to visit the gravesides of loved ones that have passed on. Cemeteries are not only for the burial of remains, but they also serve as a place for those of us still alive to remember and cope with the loss of our loved ones. Cemeteries are a peaceful place to reflect on life.

I have become a grief counselor of sorts to friends and family over the years. I understand the grief process; I am a very empathetic person, offering strength and comfort to all. Sometimes all someone needs is an ear to listen and a shoulder to cry on. I’ve often thought about pursuing grief counseling as a career, but I do believe I’ve found my calling as a writer.

Perhaps I am an old soul and that is how I accepted death without it having to be explained to me by one of my older relatives. Maybe it’s because I read a lot as a child and was exposed to death in many of the books I read; whatever the reason, I am thankful that I have that balance and understanding in my life.

Mourning and grief are such deeply felt and personal experiences that vary with each individual. We should always remember to never judge a person because they are not reacting the way we think they should – that person could be falling apart and crying on the inside.

Perhaps that person is like myself and understands that every journey must end and we should celebrate and live life to its fullest – after all, we will never get out of it alive.

*****

Laura Bock is a freelance writer and photographer. She lives her life with no fear and has taken the leap of faith many times over, which explains her sometimes wounded wings. She’s recently learned to de-clutter and simplify, so that she might pursue the life she so desperately craves. Her passions are writing, travel and photography. You can connect with Laura on Facebook, Twitter and her blog, Tales of a Formerly Inadequate Fat Girl.

Unempty Moments

Aly, her mother and grandmother

I can’t remember anything but her underwear.

I can’t remember the day or even which convalescent facility we were in. I can’t remember what my mom was telling me or what I was wearing.

What I can remember is her underwear. They were big, literally granny panties. Soft cotton. Conservative white and new baby pink. No lace or ruffles.

I can remember how they folded softly in my mom’s hands. She caressed them absentmindedly as she spoke.

We were moving my grandmother into a new facility.

We were in the repeat-the-same-question-every-five-minutes stage of her dementia, not yet to the frantic wheelchair racing or the evergreen season of suspicion. She hadn’t yet looked desperately into my eyes and asked if I could find her mother.

Aly and her mother

But still, we were scared, my mom and I. Missing the mother and grandmother we once knew. The woman who remembered her legendary spaghetti and meatballs recipe and walked loops around her apartment complex with friends bearing names like Petey or Marge.

The fear hung silent between us as we unpacked her clothes, a few books, some pictures of toothy grandchildren for her bedside table.

Henri Nouwen talks about patience as one of the cornerstones of the compassionate life; impatience the deterrent that keeps us tapping our feet, checking our watches, and missing the glory of God.

By this point in the story, (like you I venture to presume) I should have been tapping my feet, checking my watch and writing off another summer afternoon as “empty, useless, meaningless.”

But I didn’t.

Aly with her grandmother

The counterpoint to impatience, Nouwen describes another rendering of time when we experience the moment as “full, rich, and pregnant.” When “somehow we know that in this moment everything is contained: the beginning, the middle, and the end; the past, the present and the future; the sorrow and the joy; the expectation and the realization; the searching and the finding.”

This was one of these moments. Watching my mom delicately fold my grandmother’s underwear. In this moment I was gripped by the thought that love need be nothing more than this simple, intimate act.

It became an unempty moment.* A moment I didn’t want to get away from. A moment filled with the glory of God.

To this day, this afternoon represents a rupture for me. A rupture that signaled not a fracture, but a deepening. A deepening love for my grandmother. A deepening respect for my mom. And a deepening gratitude for every humdrum moment-turned-miracle I had left with both of them, together in one room, folding underwear, in an unempty moment.

****

*Precious moments was already trademarked.

****

Aly Lewis is a twentysomething writer from San Diego, Ca. When she’s not writing ridiculously witty and yet still thoughtful and inspiring copy for the international non profit Plant With Purpose, you can find her roller blading, showing off her dope hip hop moves, or overanalyzing her quarter life crisis. She has a passion for social and ecological justice, anyone who speaks Spanish, and experiencing the God of the unexpected. You can check out her mismatched musings on life here: http://memoirsofalgeisha.blogspot.com/.

And make sure you are one of the first followers of Aly’s newly hatched Twitter account!