Thoughts on John McCain’s Cancer Diagnosis and Why Death Positivity Needs to Reframe Cancer Talk

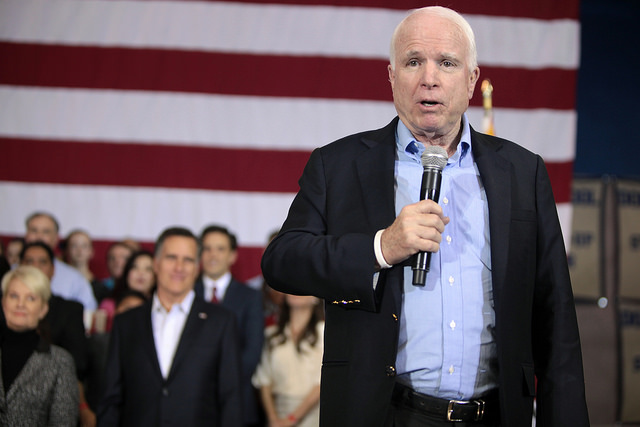

Author: Gage Skidmore

Author URL: https://www.flickr.com/people/gageskidmore/

Title: John McCain & Mitt Romney

This week we were informed that Senator John McCain was diagnosed with malignant glioblastoma. The median survival for patients with malignant glioblastoma is 14 months, while roughly 10% of those diagnosed live up to five years.

John McCain is the definition of brave. He was a prisoner of war in Northern Vietnam for five and half years. For over a year of McCain’s imprisonment, he was beaten continuously, sometimes twice a day, in an attempt to break him. As a result of his beatings, he’s is unable to raise both of his arms above his head. Despite the brutality that he suffered for being an American sailor, after his retirement from the Navy he continued to serve his country as a congressman and senator from 1982 until today.

Naturally, knowing John McCain’s history as a sailor and tenacious public servant, the language that people have used to encourage him after his cancer diagnoses have mainly been war language. President Obama tweeted this:

John McCain is an American hero & one of the bravest fighters I’ve ever known. Cancer doesn’t know what it’s up against. Give it hell, John.

— Barack Obama (@BarackObama) July 20, 2017

It only makes sense that we’d use such language for a warrior such as John McCain, but, oddly enough, when it comes to cancer, most of us default to war language for the stay-at-home mom who has breast cancer, for the auto-mechanic with lung cancer, for the construction worker with skin cancer.

We say things such as this:

“John is fighting courageously against cancer.”

If John’s cancer goes into remission, we say something like this:

“John beat his cancer”

And if someone dies from cancer, we see obituaries state,

“Sadly, John lost his battle with cancer.”

There are a couple problems with this cancer language, problems that need to be informed by death positivity. When we start from the basis that we are mortal, war metaphors start to fail because mortality is our lot, it’s a part of who we are and fighting against this aspect of ourselves leads to this fragmentation, where we assume that death is something other than us, something that is foreign, something that needs to be battled, something that we need to fight against. We are both alive and mortal and instead of seeing our mortality as foreign, the better way and the better language is to see our mortality as part of our journey. We are journeying through cancer treatment, we are still living our life amidst our sickness, we aren’t letting cancer define us, nor are we letting “the battle” define us.

Writing for the Guardian, terminal cancer patient Kate Granger summed up this idea of embracing our mortality when she wrote this:

Some days cancer has the upper hand, other days I do. I live with it and I let its physical and emotional effects wash over me. But I don’t fight it. After all, cancer has arisen from within my own body, from my own cells. To fight it would be “waging a war” on myself …. As a cancer patient who will die in the relatively near future, I believe rather that instead of reaching for the traditional battle language, [life] is about living as well as possible, coping, acceptance, gentle positivity, setting short-term, achievable goals, and drawing on support from those closest to you.

Certainly, we love life. We want to see our children get older, we want to be around our friends, but sometimes with cancer, it’s okay to accept that we will die. It’s okay to stop the treatment, not because we’re “giving up the fight” but because we recognize that we’re mortal. You’re not “losing the battle” when you have terminal cancer and you decide to forego further treatment. In fact, sometimes the brave act is in accepting the future, accepting the terminal prognosis and deciding to live your life to the fullest sans the body breaking treatment of chemo and the rigors of doctors visit after doctors visit. If we use the journey language, we recognize that it’s not about who lives the longest, but who lives the best. It’s about the best journey, not the farthest journey. It’s about living life to the fullest, not living forever. The language of journey reframes our understanding and it takes away the shame and possible guilt one might feel if we use terms like “losing the battle” and “giving up.” You are not “giving up” if you decide that it’s best to stop your treatment, it could be said that you’re bravely living your journey.

Finally, if you die of cancer, you didn’t lose. This idea that you’re somehow a loser if you die from cancer is perhaps the biggest problem with war language. Kristen Garrison writes:

How can a woman with metastatic bone lesions read Lance Armstrong’s story of conquering the disease and feel anything but failure? His story may be true, but does not represent the average person, and such narratives, which get so much press attention and bookshelf space, undercut the comparably determined but unsuccessful efforts of people fighting cancer.

Let’s bring this back to John McCain. John won’t be a loser when he dies from this cancer. He was and will continue to be a lauded individual who served his country in multiple fields. He was one of the bravest soldiers during Vietnam. And dying from cancer that will kill him won’t change that. Neither will it change you or me if our fate is the same. Some of the best people have died from cancer, and some of the worst people have managed to find remission. My journey, your journey, and John McCain’s journey will not be said to be a lost battle at our very end. This is our lot. This is who we are. We are mortal. And our character and our journey will be defined by our choices, not random, abnormal cell growth.

If you want to learn more about a death positive narrative, I have a book recommendation for you:

This entry was posted by Caleb Wilde on July 22, 2017 at 1:47 pm, and is filed under Dying Well. Follow any responses to this post through RSS 2.0.You can leave a response or trackback from your own site.