Caleb Wilde

(218 comments, 980 posts)

Posts by Caleb Wilde

More Info on “The Most Beautiful Gravestone I’ve Ever Seen”

I posted this photo on my Confessions of a Funeral Director Facebook Page.

Many have asked, “Where is this gravestone located?” ”Who is the gravestone for?” And various other questions.

Here’s Matthew Stanford Robison’s “Find a Grave” page that will answer most of your questions:

| Birth: | Sep. 23, 1988 |

| Death: | Feb. 21, 1999 |

This unique monument shows the young boy jumping upward, out of his wheelchair. Confined to the chair most of his young life, he is now free of earthly burdens.“And then it shall come to pass, that the spirits of those who are righteous are received into a state of happiness, which is called paradise, a state of rest, a state of peace, where they shall rest from all their troubles and from all care, and sorrow.” Peacefully in his sleep on Sunday, February 21, 1999, our cherished son, brother and friend, Matthew Stanford Robison was received into a state of happiness, and began his rest from troubles, care, and sorrow in the arms of his Savior and friend Jesus Christ. Matthew was a joy and inspiration to all who were privileged to know him. He was a testament to the supreme divinity of the soul and an embodiment of the completeness our spirits yearn for. The godliness of his soul inspired, influenced and blessed all who knew him. He came into this world as a miracle and left this world as a miracle. Born with severe earthly disabilities on September 23, 1988 in Salt Lake City to Johanna (Anneke) Dame Robison and Ernest Parker Robison. At birth, Matthew’s life expectancy was anticipated to be only hours long. However, fortitude, strength, and endurance, combined with the power of God allowed Matthew to live ten and one-half years enveloped in the love of his family and friends. His family was privileged to spend time with him here upon earth, to learn from his courage and marvel at his constant joy and happiness in the face of struggle. His family will be eternally changed by his presence and temporally changed by his passing. His presence inspired all those who knew him. He opened their hearts as well as their eyes. He is survived by his parents: Ernest and Anneke; sisters and brothers, Korrin, Marc, Jared, and Emily of Murray, Utah, and Elizabeth (Czech Prague Mission) Also, grandparents and other family members. A heartfelt thanks to his special care givers, especially Shauna Langford, and others at Liberty Elementary School. |

|

| Burial: Salt Lake City Cemetery Salt Lake City Salt Lake County Utah, USA |

|

Here is part of Matthew’s obituary:

For Sandy, once more…

by Shane R. Toogood

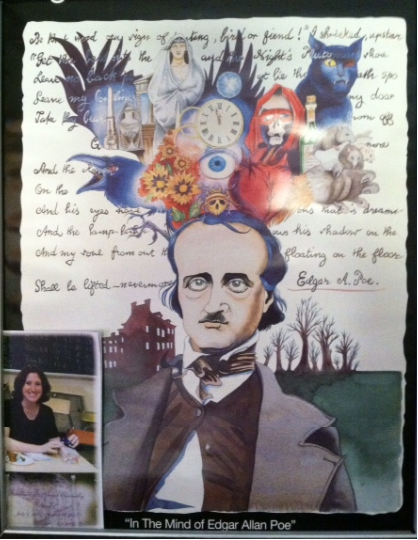

Above my television, ten years after Mrs. Connelly had given it to me, is a poster of Edgar Allan Poe: “In the Mind of Edgar Allan Poe.” It’s a portrait of the Master of the Macabre with images of his greatest pieces bursting from his cerebellum and into the world: the nevermore raven, the black cat Pluto with his one eye, the gold bug crawling over his monstrous forehead…

She and her husband, Chris, had visited the Poe Museum in Philly and, as a graduation gift, she gave me the poster. (“I hope you didn’t already have one–I couldn’t remember if you said you had been to the Poe House or not.”) That following fall Sandy would be starting her new teaching job at Delaware County Community College, the same school I was heading. Knowing I’d have a friend in the halls made going to college easier.

*

The usher pointed to a parking spot as I rolled up to the funeral home in my friend’s car. He let me borrow it so I could properly pay respects to the family. In person. It was important for me to tell them that their loved one was mine, too, but I didn’t want to intrude, only having met Chris once in high school. Didn’t he have a beard and glasses? Wore flannel? I thought about her two sons. They wouldn’t be there, would they? I imagined telling them, four and six, who their mommy was to me.

Should I just keep driving?

When you work in the funeral industry, even if it is just answering their phone calls, you get a bit desensitized. Just to cope. And before March of this year, I hadn’t cried in almost ten years. Not even at my grandmother’s funeral four years ago. For awhile I thought I had a steel heart or was border-line sociopathic.

Stepping into the parlor, alone, I blended with the others, now knowing what it was like to be the person on the other end of the phone. A female usher handed me the program: smiling Sandy on the front, opening a present at a school desk, presumably Upper Darby High School.

I smiled back.

Whether you believe in a diety or fate or some collective, cosmic consciousness, I was meant to see Sandy a few months ago at Bertucci’s. I was there with friends, waiting to be seated. First I saw Gina with her infant son, leaving. She and I became friends before I even took her creative writing classes at the community college. We caught up before she pointed beyond the wall: “Sandy and Bonnie are here.” Bonnie mentored me on the school paper at DCCC. “They’re in the back.” Bonnie, Gina and I kept in touch via Facebook, but Sandy, I hadn’t seen her in a while.

Later, as my friends and I ate, I noticed Bonnie, their colleague Denise, and, finally, Sandy walking out of the dining room. She placed her hands in prayer position over her mouth and then put out her arms. I couldn’t get to her fast enough. She seemed to be fighting back tears, friends-never-forgotten.

Her hair was cut short, not her usual shoulder-length bob, and her once Snow White skin was now rouged–but that could’ve been the lighting. The soft down of her new cut brushed across my cheek. It’s great to see you, I told her. I’ve been meaning to write. I finally graduated college!

“Ooo, that’s good,” she cooed, still smiling. I debriefed her on the past few years and told her I’d write. She told me, “I’d like that.” We said goodbye.

Smiled.

Goodbye.

*

“She has been quite ill in the last year and a half and has taken a turn for the worse in the last couple of weeks…” Gina’s Facebook message wasn’t a shock so much as it was thirty-nine lashes across the face. When I saw Sandy at Bertucci’s I thought she looked different, but she was fine. I was being silly to think she was sick. She would have told me, right? “Though she is not able to read emails, her family can read letters to her.” Do it now, I told myself. Easter Sunday, 2013, I lost another friend and mentor, the New Hampshire Poet Laureate Walter Butts. The letter I started for him still stays folded in my Trapper Keeper, unfinished. It was too late. By the time I started the letter, only a few days after learning he was ill, he was gone.

*

The guest book. A phrase I hear so often at work–is the guest book provided by the funeral home or is it included in the price? I’m not sure, but I can have the director call you right back–would now bear more meaning. My heart was beating so hard my body shook as I attempted to sign my name in a straight line in the guest book. For Sandy, once more…

Once, in the middle of a class assignment my freshman year in high school, Sandy walked over to me with a pen in one hand and the school’s purple lit mag in the other, beaming. My short story had just been published.

Kneeling down, she placed the open magazine next to my composition book and asked for my autograph. Some of my peers looked up from their papers, making me a bit self-conscious at first, but when she told me she couldn’t wait to tell people she knew me once (something any writer wants to hear), I proudly scrawled my name. I knew it then, and I know it now, had I never had the privilege of knowing Sandy, becoming friends with her, I might not have known what to do with my life. She was more than a dear friend and mentor: Sandy is an integral part of who I am; she prodded the “me” out of myself. For that, I will be forever grateful.

We essentially followed each other to DCCC where, between classes, she and I would talk in her office. Told me to call her Sandy because she hadn’t been my teacher in quite some time. When I graduated from DCCC, a few of her colleagues would joke with her: “You following Shane to Goddard, too?” She’d laugh. Say she was looking for a position. And of course I wouldn’t have minded; at least I’d always have an office to visit.

Time was eternal idling in that line. Watching the slideshow on the flatscreen, I immediately suppressed even the slightest inkling of a lip-quiver. Not here, Shane. Not in public. The Pina Colada Song and Brown Eyed Girl played…played…played…until I was forced to burrow my own earworm with Edward Sharpe & the Magnetic Zeores’ “Two.”

I practiced what I’d say in case I got choked up when introducing myself to the family. At work we’re prompted to offer condolences, but it never gets any easier. Chris, my name is Shane Toogood. Sandy taught me in high school. She really encouraged my writing, and through that we became friends. I could see him standing next to the casket: no beard and light hair. Where did I conjure up this remembrance of a hipster with dark-rimmed glasses and a bushy beard?

The funeral home was very comforting with framed pictures of Sandy and her family on the tables making it feel more like we were in her own home. Typically I don’t view bodies. Not up close. And I realize now that it’s not being around the dead that made me feel so uncomfortable for so long, it was not knowing what to tell the family. My name’s Shane and I was a friend of Sandy. I’m so sorry for your loss. I kept a watchful eye, hoping to see at least one familiar face. Bonnie and Gina said they’d be there. A few of Sandy’s colleagues trickled in, but they were too far or too distraught to notice me. (Remember me?) Before I left the house I thought about texting Gina that I was on my way, hoping it would entice her to wait for me. We could go in together, and then maybe she could explain to the family who this tall stranger is.

I was around the corner now, the casket twenty feet from me. A stuffed Super Grover was propped at the bottom, waiting to take flight over the the purple casket spray draped over the top.

Aside from some chattering and the skipping songs, the funeral home was quiet, somber. Then I heard a burst of crying up front. I looked towards the family. First I saw Bonnie talking to Chris’ parents. Then Denise. And there was Gina, wearing sunglasses, rocking with Sandy’s mother. Sandy lay in the casket.

Bonnie made her way over, her arms waiting to catch me. Sandy had urged me to introduce myself to Bonnie, knowing she could help me with my writing. Plus, “Bonnie has had a few publications,” she said. My chest sputtered like a car engine trying to turn over. I turned away, suddenly not sure if I wanted her to see me or maybe I knew that if I saw her, this pressure building inside of me would burst and I’d leak all over.

Bonnie wrote: “Shane, I have very sad news.” This was last Thursday. “Sandy Connelly passed away last night…This is truly heartbreaking.” Heartbreaking. I never knew the impact, the density of the word, until it crushed me breathless. A word tossed so loosely, like dirt off a shovel, now gained meaning.

We didn’t say anything, just cried in each other’s arms.

Bonnie expressed her love for my online condolences. She asked Denise, putting an arm around her shoulder, if she had read it. She hadn’t, so Bonnie recapped the story of the autograph. We all fought back tears, using bunched up tissues to stop the flow.

I folded over to hug Gina and we whispered how deeply sad we both were. Finally, I could let go, grieve with the ones who knew my pain. The ones who cried on their beds, too, hoping their sobs would rock them to sleep. The ones who turned up the music to drown out their crying, but just the same hated that the songs were playing.

My dry mouth, I could tell, smelled like decay. I needed a mint. There were bowls of them everywhere, wrapped in mute silver plastic. A mint could help coax out some H2O. Another one of my past professor’s joined the huddle. “Oh, Shane.” She looked at me over her glasses, telling me how much Sandy loved me. They all told me.

The mint wrapper crackled in my fumbling hands. I hoped it was spearmint. But instead of a Golden Ticket I found a lone chocolate. Better than nothing. I bit down. A dry dinner mint crumbled like ash beneath the chocolate coating.

I needed a mint!

*

Writing Advice. “Of all the things you’ve written…I think that horror is the best,” Sandy once wrote to me. This was her polite way of telling me that the modern tale of unrequited love I wrote for a girl I was courting in high school was complete shit. I heeded her advice.

*

My heart was pounding. I stood beside the open casket, admiring how beautiful Sandy looked, holding her purple rosary beads. Just the way I remember her. The first time without a visible smile. Two people away. But her presence was still warm.

Chris, I’m so sorry for your loss. My name is Shane. Sandy and I were friends from Delaware County Community College. Chris’ eyes met mine. Or so I thought they did. I gave him a sad smile, to both acknowledge I saw him and that I was sorry for his loss. Next. My body stopped producing saliva after I drained every ounce of water from my body onto Bonnie’s shoulder.

Chris, my name is Shane. Toogood? Sandy taught me at Upper Darby and we remained friends since…I opened my mouth to speak.

Chris put out his hand. “Shane, right?” I shook my head, walked a few inches. He was taller than me which, in that moment, seemed so appropriate. “Sandy told us so much about you.” He told me about how much she and the family loved the letter I sent a few months ago. How much Sandy loved it. I was on auto-pilot, trying to think of things to say. To respond. Bonnie and Gina’s voices lingered in the back of my head. Are you by yourself? Are you going to be okay? I hope so, I kept saying. “And you didn’t know she was sick?”

“I did. Gina reached out to me,” I told him, immediately wanting to offer a retraction. Should I have lied? Told them I didn’t know? If not to protect the family’s privacy, but to protect Gina’s confidence? “But I didn’t know it was this bad.” Chris said Sandy didn’t think I knew, and I was glad. After Walter’s death, I wanted to reassure her how much she means to me anyway; it’s better that she rest in peace thinking I was ignorant. Sandy’s mom nearly jumped up and dangled from my neck when Chris introduced us. She told me she loved the letter. Sandy loved it. “We all love that letter! We’re going to put it up in a frame.”

Her father reminded me that we had met when the U.S. Poet Laureate visited the college. “Kay Ryan! That’s right!” He was glad I came. They made me feel at ease and I could sense Sandy’s love through them. And when I tried to offer my condolences, each family member would instead tell me how I affected Sandy. “Just know that you meant a lot to Sandy,” her sister said. I do, I said, feeling that I know Sandy so much better.

*

Above my television, ten years after Sandy had given it to me, is a poster of Edgar Allan Poe: “In the Mind of Edgar Allan Poe.” It’s a portrait of the Master of the Macabre with images of his greatest pieces bursting from his cerebellum and into the world: the nevermore raven, the black cat Pluto with his one eye, the gold bug crawling over his monstrous forehead…and stuck between the frame is a funeral program boasting the picture of a friend opening a present, melting ice cream cake beside her, and an effervescent smile that will never fade.

****

Shane earned his BFA in Creative Writing from Goddard College. His fiction and articles have been published in various newspapers, blogs, and lit mags including the Philadelphia Inquirer and, most recently, the inaugural issue of the Philly Anthology, Vol. 1.

Same-Sex Marriage and Death

What if you were told that your spouse cannot be buried next to you?

Or that you’ll have to pay a large tax bill upon your spouse’s death that your neighbors, who have been married a shorter time than you and your loved one were, won’t have to?

Though the tide has begun to turn, these are among the struggles that same-sex couples have had to face for years, and the hurdles which these couples have had to face serve as a reminder to all of us that with the inevitability of death, we have to strive to make our end-of-life wishes are known and that they can be fully carried out.

Imagine you get a call from your spouse’s sister that your loved one has taken a turn for the worse at the hospital, and the doctors expect them to die very soon. You rush to the hospital, but find that not only will the doctors not tell you what’s going on, but you are barred from entering the room where your partner of 25 years lay dying. For many, this heart-wrenching scenario was all too real until 2011, when the federal government issued a directive that all hospitals that receive federal aid must allow people to designate those who can visit or speak for them in the hospital. Sadly, as recently as this year, there have been cases where individuals have had those rights infringed upon by individual hospitals.

While the movement for same-sex marriage has gained ground on a state-by-state level, with 13 states, the District of Columbia, and several federally recognized Native American tribes all issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples, there were until recently many hurdles on the federal level – and the dust is far from settled in Washington. Add to this the states that have passed laws expressly forbidding same-sex marriage, and you’re potentially adding layer upon layer of struggle on top of the grief someone experiences at the death of someone who has stood by them for years.

Even as the United States Supreme Court ruled that the federal Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) – passed in 1996 and defining legal marriage as between one man and one woman – unconstitutional in June, the picture for same-sex couples became even murkier. Suddenly, depending on which part of the federal government you asked, you were either entitled to benefits or you weren’t. The same week that DOMA was ruled on by the Supreme Court, the Department of Defense began providing equal benefits to same-sex couples, including death benefits.

Among these was the right for same-sex spouses of those eligible to be buried in Arlington National Cemetery. However, the majority of the remaining national cemeteries in the United States are overseen by the Department of Veterans Affairs. It wasn’t until the beginning of September that the VA was directed to begin offering all the same benefits to same-sex couples that others had been entitled to for years, including the right to be buried in a national cemetery operated by the VA’s National Cemetery Administration. In fact, before that directive from the Department of Justice, same-sex couples had to apply for special waivers for burial – and only one had ever been granted. With such dissonance between two parts of the same government, there are no doubt still hurdles to climb and red tape to cut!

Also, in late August, the IRS announced that it would treat same-sex spouses married in states that recognize their marriages for tax purposes, even if the couple officially resided in a state that either does not recognize or officially bans same-sex marriages. These couples can now file jointly, and are entitled to all the same federal tax benefits other married couples are.

Though there have obviously been significant steps forward for same-sex couples in the last few months, the recency of these decisions may still lead to a great deal of confusion for many, and the pace and inconsistency of these changes highlights the fact that, regardless of legal marital status, it remains vitally important for everyone — especially same-sex couples — to discuss end-of-life issues with their loved ones. Do not simply assume that because you hold a marriage license and are extended certain benefits, you’ll be extended those benefits and courtesies across the board, regardless of where you are in the United States. Communication has long been cited as an important component of any long-lasting, loving relationship. Put those skills to use. Talk to each other about your wishes and write them down.

Avoiding talking about death and dying doesn’t postpone the inevitable, and especially in cases such as the ones mentioned above where the law has been rapidly evolving, it can make things even more difficult. You’ve been partners throughout life, supporting one another no matter the hurdles along the way. Don’t shrink from that teamwork now. Do all that you can to help prepare one another for all of life’s events – especially the ones at the end of it.

*****

Today’s guest post is written by my friend Chad Harris. This from Chad: I’m a graduate student at Hood College in Maryland, where I am pursuing coursework in thanatology for eventual certification as a thanatologist and death educator. Upon graduating (hopefully in May!), It’s my hope to work with military families and veterans, a passion I first discovered while working within the Department of Veterans Affairs health-care system.

Today’s guest post is written by my friend Chad Harris. This from Chad: I’m a graduate student at Hood College in Maryland, where I am pursuing coursework in thanatology for eventual certification as a thanatologist and death educator. Upon graduating (hopefully in May!), It’s my hope to work with military families and veterans, a passion I first discovered while working within the Department of Veterans Affairs health-care system.

I also have a master’s degree in social work from Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, and a bachelor’s degree in journalism from the University of Central Arkansas.

Warring Against Death

I make really odd faces when I’m asking questions. In fact, my face is so scary that the NSA has banned my face from the internet after this post. “Next time, wear a mask” they said.

As you might imagine, with a face that frightening, it was next to impossible to get my interviewee to be relaxed and comfortable. Especially when I started the interview with the statement, “Sup. I’m Caleb. I’m a funeral director.”

Alma – the lovely lady I interviewed through a translator – is World Vision’s Guatemalan National Sponsorship Coordinator. Her and her team keep track of the 60,000 sponsored children in Guatemala.

She was a sponsored child from the age of five through twelve (she told me she still has the photos of her sponsors in her office desk) and credits World Vision for sponsoring her early schooling; schooling that eventually culminated in a bachelor’s degree in education.

Alma’s very proud of the fact that her children are not sponsored children. She’s proud because her life embodies the story that World Vision is attempting to reproduce; a structure of support that eventually produces self-sufficiency, where World Vision helps people stand on their own. She embodies the best of the World Vision sponsorship program, so who better to lead it?

After making a number of awkward faces while prodding about her life, I made the conversation even more uneasy when I opened up my series of questions about death.

We talked about funeral practices in Guatemala and thankfully Alma understood enough about American culture to provide some contrasts by explaining that there’s no embalming and there’s rarely a funeral director involved in rural Guatemala. Most funerals are at home and for many there’s no casket involved.

Alma told me that the body is carried to a local graveyard and for nine days after burial the family is in mourning, donning black clothes.

I then asked her, “What about children?” It’s here she begins to show some emotion. The conversation moved past information exchange as we reached the heart of her job.

I know some poverty stricken cultures will forgo naming children until they reach a couple months of age. Where infant mortality rates are high (like Guatemala), an unnamed child means less attachment, less love and less grief. With that understanding I didn’t want to assume Guatemala had infant funerals, so I asked, “Are there funeral customs for children?”

“Yes, there are.”

As the conversation trekked onward, I could tell that I was getting close to the need that inspired her passion.

“And what,” I asked with my ugly face, “is the leading cause of death for Guatemalan children?”

“Malnutrition and preventable sickness” came out of her mouth as though she spoke the name of an enemy. An enemy that was ever present in her mind. An enemy that was as close to her as a lover. An enemy that went to bed with her, that walked with her to work and that motivated her 10 to 12 hour work days. Anger, even hatred, contorted her face as she described how dysentery, “common” infections and even a simple cold will blow out the promise of a new life. How a lack of food will starve a child in the rural areas of Guatemala where work and a nutritious diet are scarce.

“These deaths don’t make me cry” she paused, “they make me angry. They are so easily preventable, so easily solved.” As we talk some more I begin to see a warrior in Alma. A woman warrior. No armor, no swords and shields, but a driven fighter set on saving children from preventable death.

I know how nonprofits work. There’s an enemy that the nonprofit stands against and that enemy is fought with the doubled edged sword of resources and volunteers. When there isn’t enough resources and volunteers, there’s casualties.

In this war – the war that Alma is fighting — the casualties are children.

“Do you feel like you have failed when a child dies?” A resounding, “No.” She says, “Because what we’re doing is a partnership. We are teaching parents to care for their children. I can only do as much as my resources allow me.”

And partnership is the key. You might not be able to volunteer, but you can provide the resources for those who do.

The picture is gut wrenching, dark and sad.

The reality is this: people in poverty need the help of you and me.

It many cases, you can’t money solve a problem. You can’t throw money at the problem and fix it. But in this case, we’re not throwing money at a problem, we’re giving it to people, to a warrior woman like Alma and I believe she knows what to do with it … she can at least save some. Help her.