Dying Well

Why I Became a Mourning Doula

Today’s guest post is written by Laura Saba:

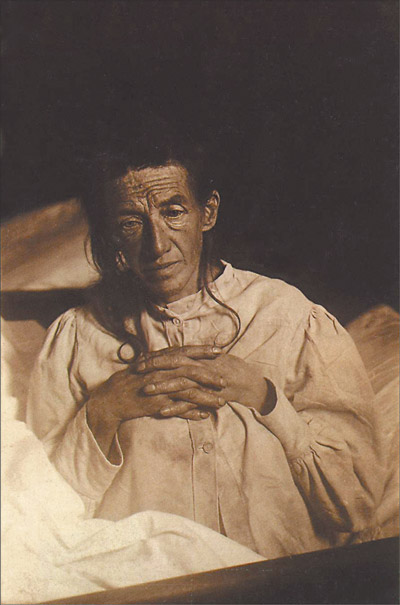

© 2003 Derrick Tyson, Flickr | CC-BY | via Wylio

I’ve been around death A LOT. When I was 4 one of my playmates, a 5 y/o, died of an asthma attack. They buried her and planted a tree at school in her memory. I couldn’t wrap my little brain around it – where did she go, and why did they plant a tree? Was she inside that tree?

A few years later, my grandmother’s tenant died, her body there on the apartment floor. Then when I was 11, my friend and I were about to deliver our newspaper route, when her mom was discovered. She’d had a stroke while leaning over to pull cookies out of the oven. Her face lying on the hot open oven door ’til found was not a pretty scene.

Flash forward to high school and you have the requisite schoolmate suicides, overdoses and car crashes. A few more years spin by and my best friend is murdered in a ”wrong place wrong time” incident, then a few years later my brother was KIA in Iraq (Semper Fi!). Then friends lost to cancer, as well as aging relatives and friends lost along the way.

My work as a birth doula also brought me into the realm of death at times. Soon I was volunteering as a loss doula, for women who would be induced due to a lost baby. There were the stillbirths. Then volunteering with Hospice, as I got really good at working with grief. Along the way I also co-owned a “Grief Gift Basket” business, where we created condolence baskets and our highly popular “Miscarriage Gift Baskets” which addressed the unspoken grief of so many women in a more honest and open way.

Along the way I often stepped in, helping others plan, assisting them as they went to make arrangements. Suddenly I knew the ins and outs of an industry I’d never been in. Too, I saw that supporting people through this process was, in so many ways, calling upon the skill-set of the birth doula, just channeled into a different high-stress time.

It became quickly obvious that people needed an advocate when dealing with this emotionally charged situation. That they needed a 3rd party, not emotionally attached to them or their dearly departed, to advocate for them, to hold their hand, to make necessary phone calls, to run clothing to the funeral home, or help figure out where that green cemetery plot is, precisely. Someone to help them hold it together as they navigate the minutiae in this complicated time – and to ensure they are fully informed, while ensuring they are also physically and emotionally supportive.

It amazed me to see that people responded to this support even more quickly and readily than they initially did to birth doula support. How was it that this Mourning Doula did not exist prior?

I realized it is because in other times we took care of our own dead. Family, friends, our villages rose up and assisted us. As with the birth industry, we need the support because these emotionally sensitive circumstances are no longer handled in the same way, but rather are almost under-the-rug-swept, as we as a culture work to dissociate ourselves from the messy realities of birth and death. Subsequently, there is the potential for someone to take advantage of our vulnerability – not even necessarily out of ill will or greed (though it too often is), but even out of good intentions.

It is simply a fact that no one knows what we would genuinely want if they don’t know us, and aren’t putting advocating for us first and foremost in their mind – especially when there is financial gain involved, it can be all too tempting to sway one in a particular direction over another. Had our culture not distanced itself emotionally and physically from birth and death, if these undertakings had remained undertakings rather than becoming a business, things would perhaps be very different at this time in history. However, as things are, this is how life is in the modern world. We have turned the very bookends that mark our lives into an industry, giving power over some of our most precious moments to others. With power comes at times corruption, and so it is we see the rise of the doula.

*****

Laura Saba is founder of Momdoulary, LLC, which provides training and certification in the Momdoulary Method of both Birth and End-of-life, Mourning, and Death Doula and Midwifery support, and Post-Loss Life Coaching, and Professional Organizing & Management of Material Artifacts Post-Loss.

Laura’s background in life & loss coaching, doula support, FEMA and Red Cross trainings, and experience providing support following natural and terror disasters, coupled with hospice volunteer support, led to a natural combination of her doula and coaching experience to provide end-of-life and post-loss support. This inclination was reinforced by extensive personal experience with loss, beginning at the age of 4 with the death of a playmate, and extending to the loss of a brother in Iraq, and numerous friends and former colleagues on 9/11.

If you’re interested in being trained to be a End-of-Life doula, Mourning doula, Death doula and/or Death Midwife, you can visit Laura’s website, Mourning Doula.