Death in the News

On that Decaying Foot that Popped out of the Ground in a New Jersey Cemetery

“I’m so overwhelmed. I’m very stressed, depressed because I’ve never, ever been to a funeral before and seen anything like this.”

The family is considering a lawsuit, and I’m not diminishing the family’s feelings or experience. After reading the article, it does seem like the cemetery could have handled things a little bit better. Although they may not have been able to stop the foot from popping out on Mr. Butler’s casket, they could have been more sensitive in explaining to the family how it happened.

If you’re interested in seeing the dirty of death, and yet the beauty of it, I wrote a book about it:

An Explanation as to Why Those Caskets Are Floating in the Louisiana Flood

You’ve probably seen those utterly disturbing pictures of caskets floating downstream from the Louisiana Flood.

It’s horrible. The stuff of nightmares.

You probably have some questions:

Why do they float?

Can those bodies be easily identified?

Shouldn’t the vaults keep them contained in the ground?

To the first question.

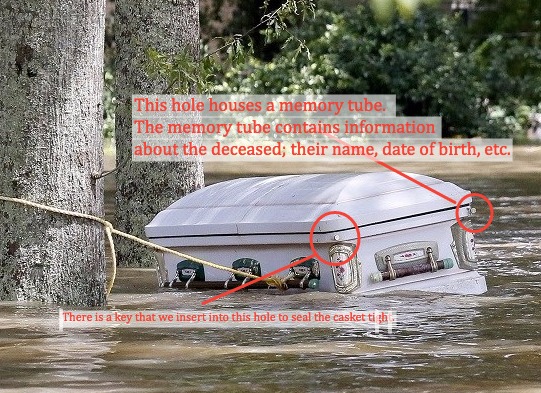

There are a couple of kinds of caskets. There are wood and metal caskets. Within the metals, there are sealing caskets (also known as gasketed or protective) and non-sealing caskets. Sealing caskets have a rubber gasket that creates an airtight seal when the sliding lock bar is cranked shut with the casket key. You may have seen funeral directors use said key after the lid is closed at a funeral. We insert it into a small crank hole at the foot end of the casket and turn it until the lock bar is totally tight.

Sealing caskets are the only ones that will float. Even though you would think a wood casket would float, because wood caskets don’t seal, they’re more likely to fill up with water and stay put in their vault.

Can those caskets and the bodies contained in them be identified?

Most sealing caskets have what’s called a “memory tube.” You can see where that tube is located in the picture below.

If the funeral home filled out the memory tube, the process of identification is a whole lot easier. If the casket doesn’t have a memory tube, the process becomes much more complex. Although I’m not certain, I can imagine that DNA testing would be the last resort.

If the funeral home filled out the memory tube, the process of identification is a whole lot easier. If the casket doesn’t have a memory tube, the process becomes much more complex. Although I’m not certain, I can imagine that DNA testing would be the last resort.

Shouldn’t the vaults keep them contained in the ground?

Most cemeteries require vaults (a requirement that I disagree with, but that’s another blog post). Vaults, like caskets, can either be the sealing type or the non-sealing type. When the ground becomes over-saturated with water, the sealing vaults can pop out of the ground, causing the vault and the casket it contains to float away (see the picture below).

More often than not, it’s just the casket that floats away. In the case of the Louisiana Flooding, the vaults are exposed above ground (I would only assume it’s because there’s a high water table in these parts of the country). If the vault was buried underground as is the case in most cemeteries, it’s less likely that the caskets would pop out. But, since they’re that much closer to the top, it’s that much easier for them to stroll down the river when the flood waters come a rolling.

If you don’t want to go boating and floating after you’re dead, there are a few things you can do to make sure your body never washes away:

- Cremation

- Green burial

- Don’t use a sealing casket

- Tie your vault to an anchor.

When you Only Find a Piece of Your Loved One

© 2010 SDASM Archives, Flickr | PD | via Wylio

Just like the life cycle feeds off of death, so does the news cycle. Anything that has a degree of tragedy usually finds its way onto the national and/or international news. In principle, many of us realize that “if it makes the news, we don’t have to worry about it” (because the news is by definition exceptional), but unfortunately the news ends up normalizing tragic deaths, causing us to have unreasonable fears.

The reality is very much the opposite. Most deaths are not tragic. Most are decent, respectful, good and natural deaths. Most dying processes allow for family and friends to say “Good-bye”. And most die at a good age. It’s easy to forget that the life expentancy in the United States is nearly 79 years. While we can’t say for certain that those 79 years were all good years, we can say that the vast majority of deaths occur at a later stage of life, after much of living has already taken place.

The normal death is usually a good death.

But when tragedies like Kogalymavia Flight 9268 occur and the 224 passengers are killed, it’s hard for tragedies not to cloud our view.

There’s some definable characteristics that make a death tragic. Suddenness, intense pain in dying, a death that happens in one’s youth, an accidental death, etc. are all characteristics that can make a death particularly tragic. Another factor is dismemberment.

If the deceased’s body is never found, it’s a tragic death that too often inspires unresolved grief; a double wammy of losing a loved one and never being able to properly say good bye to the physical representation. A dismembered body is often a dismembered grief.

I’m often noticed how important it is for families just have the solace of knowing the body, or even a piece of the body of their loved one has been found. It offers some degree of peace, some degree of knowledge that their loved one is indeed dead. A missing body seems to produce an unresolved grief, where the question always seems to exist: “Did he/she survive? Are they still out there?” Accepting the death of a missing loved one is made that much harder when the there isn’t a physical dead body to provide that visual wake-up call.

When I see tragedies like Flight 9268 and the incredibly intricate process of determining remains (as small as they may be), I’m again reminded of the healthiness of viewing the body of the deceased. Please understand, I’m not necessarily promoting embalming, but I am saying that the value of seeing the deceased at some point seems to provide a legitimate psychological aid in death acceptance. Part of the reason that cremation can be unhealthy is that there’s times when we don’t get to see the deceased as dead. The body is whisked away to the crematory never to be seen again. There’s value in making that extra effort to see a loved one as dead.

When I consider the families of those lost in this most recent plane crash, I both recognize how tragic it is and I’m slightly thankful that I’ve been privileged to see the bodies of my loved one.

What does is say about us? On the Live Murder of Reporter Alison Parker and Photographer Adam Ward

I admit it. I watched the video. Both videos. I watched the live feed that was broadcast on TV. And I watched the murderers’ video that he would later upload after he murdered Alison Parker and Adam Ward.

Both videos were horrific. Both were extremely sad.

After watching them, I found myself asking “why?”. “Why did I watch the videos of Alison and Adam’s murder?” It says something about me. It says something about us that the video would find its way onto nearly every major news feed and that millions of people were compelled to watch a tragic murder unfold.

But, I’m not entirely sure what it says about us.

We’re all intrigued by death, especially the tragic kind. We want to see what a real life shooting looks like. Does it REALLY look like the stuff we see in the movies, with Dexter-like blood spatter flying everywhere and the victims shouting in agony? Do the murderers engage in an angry soliloquy before taking the lives of their victims?

There’s a healthy tension between the sacred and spectacle of death. Death is sacred because it’s a very personal chapter in a person’s (and family’s) narrative; but it’s a spectacle because many of us have the desire to funeralize in a public forum. Most deaths tend towards a sacred, private sphere, while some deaths – like the death of Michael Jackson, Whitney Huston, Heath Ledger, Kurt Cobain, Robin Williams, etc., etc., etc. – have such a sweeping public dimension that families and friends are left grasping for privacy amidst the spectacle.

This sacredness of death is the reason so many of us hate the Westboro picketers, who picket the funerals of fallen soldiers, and any other funeral that can grab them some limelight. We dislike what they’re doing because it transgresses one of the most sacred aspects of both our love and our humanity: the grief that comes from the loss of personal love.

Today, broadcast before the world, we witnessed the deaths of Alison Parker and Adam Ward. That is, after all, what the murderer wanted. He wanted his anger and his hatred to steal away the privacy of two individuals, robbing them of a sacred death and instead making their deaths entirely into a spectacle.

He did it.

I bought into it.

We bought into it.

We now know Alison Parker and Adam Ward as the people who were murdered on live TV.

What does it say about me? What does it say about us?

Perhaps it says that “death as spectacle” has become normalized. Perhaps it says that we’ve been robbed of the sacredness of death. Perhaps the death voyeurism that we’re constantly feed by the media, by video games and movies has caused us to move death out of the realm of the sacred and into spectacle. Perhaps we’re more used to death as spectacle than death as sacred.

My Thoughts on the Transgender Woman Presented as a Man at Her Funeral

As a preface, let me say that I’m thankful to have transgender friends, who have graciously helped my vocab and have helped me to become more sensitive to the trans community. And yet, I know I still have things to learn; so forgive me if I misstep in any of my verbiage.

Here’s the story from the Miami Herald:

Jennifer Gable, an Idaho customer service coordinator for Wells Fargo, died suddenly Oct. 9 on the job at age 32. An aneurysm, according to stunned friends.

Just as shocking, they say, when they went to Gable’s funeral in Twin Falls, Idaho, and saw her in an open casket — hair cut short, dressed in a suit and presented as a man.

Gable was transgender, born Geoffrey, but living the past few years as Jennifer

The simple tragedy of the story is this: Jennifer died suddenly at an age when she had probably never thought to assign the power of her funeral arrangements to an entrusted friend (something she could have done in Idaho). And because she didn’t designate a person to arrange her funeral, it fell to her legal next-of-kin; which, in this case was her parents.

The fact that her parents dressed Jennifer as a man and used the masculine pronoun in the obituary, as well as Jennifer’s previous name “Geoffrey” in the obituary shows that her parents couldn’t accept Jennifer; they wanted Geoffrey.

Whether you choose to accept Jennifer as a transgender female or not, you will probably agree that there’s something wrong with her parents presenting her as a man in death. The problem is this: our death-style should reflect our life-style. In fact, you could say that the deceased is honored when the death-style reflects the life-style.

And when Jennifer’s parents attempt to hijack Jennifer’s narrative and determine the death style based off their wishes (and not hers), this act is dishonorable to Jennifer’s life.

These kinds of struggles happen: the legal next-of-kin doesn’t agree with the deceased’s lifestyle and finds themselves in this dilemma: “Do I honor the deceased in death? Or, do I recreate the narrative to something I’m more comfortable with?”

Whether it be religious disagreement, political disagreement, lifestyle disagreement or the kind of disagreement that Jennifer’s parents had, I think we should see the integrity in honor.