A Letter to the Good Funeral Director Working at a Bad Funeral Home

Author: Stephan Ridgway Author URL: https://www.flickr.com/people/stephanridgway/ Title: Raj’s funeral Year: 2011 Source: Flickr Source URL: https://www.flickr.com License: Creative Commons Attribution License License Url: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/ License Shorthand: CC-BY

You joined this business because at some point in your life you realized that you could do something good in death care.

Maybe you lost a loved one, and you wanted to use your pain and experience to help others walk through the difficulty.

Maybe a funeral director’s love and helpfulness inspired you to want to be the same.

Maybe you felt called to the dismal trade, knowing that deep inside you resides a resilience that few other people possess.

Whatever your reason for working in death care, the end was clear: you pursued this profession because you knew something good could come of it.

Then you started to look for a job. And the market was much tougher than you realized. The business was harder to crack than you could have imagined. The family-run funeral homes that you wanted to work for didn’t have any open positions. And the large, machine-like homes only offered positions with tough hours and cheap pay.

Whatever your story, you either ended up at a funeral home that you thought was great, or you ended up at a funeral home that was less than ideal.

*****

For some of you, you worked your way up from the bottom. You put in your due. The night shifts. You worked on holidays. You cleaned the prep room. You parked the cars. You mowed the lawn. You worked with Larry, the son-in-law of the owner who constantly makes off-color and sometimes sexist jokes.

Or maybe you got stuck with Robert, the owner’s nephew who slacks off, rarely pulls his weight, and constantly complains.

Then there’s John/Johanna, the supervisor. When he/she’s in front of the public, he/she’s the consummate professional: caring, compassionate and consistent. But when he/she’s out of the spotlight, his/her ability to supervise is nowhere near his/her ability to be a funeral director. His/her temper is short, he/she blames failures on everyone else except himself/herself and the only time you’ve ever seen him/her smile is when he/she’s bragging about himself/herself or leaving for vacation.

You’ve finally worked your way up the ladder and now you’re making arrangements … doing the thing you’ve always wanted to do.

Except, you’re not just expected to care for people, you’re expected to care primarily for the bottom-line of the business. The tag-line of the funeral home would imply that families come first, but the truth you’re realizing more and more is that it’s really the dollar.

Upsell the caskets.

Upsell the packages.

Push embalming.

Obfuscate, obfuscate, obfuscate so that families don’t know the money saving options.

Use lines like, “This is the casket your loved one deserves.”

And, “This casket honors your dad’s life like no other.”

Or whatever line the kids are using these days.

*****

First off, if this is you, I’m sorry.

Unmet expectations are difficult to digest. Lousy supervisors make a difficult job even more demanding. And finding out that — for some funeral homes — it really ISN’T all about service … finding out that many of these dudes are in it for the money … that discovery is enough to deflate the reason you pursued this career in the first place.

There’s a couple options for you at this point: Sometimes, the good funeral director in a bad funeral home holds onto his/her job. They kowtow to the system because — let’s face it — it might not be the best income, but it’s a job.

Some quit. Let me correct myself … many quit. They’ll go looking for a better funeral home with better people. And those funeral homes are out there. They really are.

Others will try to start their own funeral home, or buy out an old one so that they can implement their original vision of what death care should look like.

But for many, they wash their hands of this industry and make the healthy choice to find another profession.

To the good funeral director currently working at a bad funeral home, I’m not going to promise you that it get’s better. Some things don’t get better. Some things need to be burnt down (I’m talking figuratively of course). Some things can be changed, through hard work and a labor of love, to be something better. Some things need to be abandoned.

Whoever you are. Wherever you’re at. Let me say this: death care needs you, but you don’t need it.

If you entered this business with a heart to serve, YOU are what families need when they encounter a sudden death and have minimal funds. YOU are what families need when they just want someone to honestly tell them their options. YOUR ability to bring some sense of order to chaos is exactly what we need.

But, let me be clear: YOUR DESIRE TO SERVE DOESN’T NEED THIS INDUSTRY. That heart to serve can play out in so many different professions. EMT. Nursing. Coroner. Medical Doctor. Anywhere, really. Because the world always has a shortage of people who genuinely want to help others, and if you genuinely want to help others, you’ll never have a shortage of opportunities.

*****

If you like my writing, consider buying my 2017 Nautilus Book Award Gold Winner, Confession of a Funeral Director (click the image to go to the Amazon page):

Never Apologize for Your Grief

Note: I was editing this post when a house call came in. I don’t think I’ll be in front of a computer until late tonight, so I present to you a blog post with even MORE errors than normal 🙂

I just got off the phone with a lady who lost her husband back in August. She called because she wanted to order an urn plaque for her husband’s urn, and was inquiring about the details. Could she put a prayer on the urn plaque? Could she put his picture on the plaque? How long would it take to make it? Could we affix it to the urn for her?

“Yes, yes, a couple days, and yes”, I said.

After we were done, she asked, “Can you repeat all that because my mind still isn’t right?”

“Sure. No problem.”

“I’m so sorry” she pleaded. “My mind hasn’t been right since Jack died. I can’t think straight and I’m stuck in my own little world.”

“You’re right where you supposed to be,” I replied. “And your mind is working just fine.”

She thanked me and I told her I’d be in touch in a couple hours to go over the urn plaque draft before we send it to our plaque makers.

I’m not a grief counselor. I do have a certificate in Thanatology, but I’m not qualified to give specific, personalized advice to anyone. I can, though, speak to this shame associated with grief. A shame that comes from a bad idea.

That bad idea is this: that there’s something shameful about feeling weak.

*****

Let’s break it down so we can eradicate it.

WEAKNESS ISN’T …

Weakness isn’t tears. Tears of grief are symbols of love. There’s an outdated idea that says strength is the ability to go through trials and remain unaffected. That we’re all supp It’s a toxic view that’s seeped into our conception of masculinity, and our concept of how we think grief should look.

Weakness isn’t grief, no matter how that grief looks. Somewhere along the way, we’ve attached timelines and a particular set of expectations to grief. There’s this idea that it’s okay to grieve for a couple months, maybe a couple years, but if that grief still exists 10 years later, there’s something wrong with you. There’s another idea that if your grief looks different than our grief, you’re not right. Grief is the outflow of love, and love is the strength of humanity. I don’t tell my parents, my friends, or the people I work for how their love should look, nor do we tell them how long they should love. But we do it with grief and it simply doesn’t make sense.

Weakness isn’t shameful.

Most of our experience that we perceive as weakness, aren’t actually weakness … they’re just very much a part of our humanity. It’s human to cry, it’s human to grieve, it’s human to feel confused, to make mistakes, to try and fail, to change your minds, to change your jobs, your hobbies, to quit, to begin a new, to dream and doubt, make mistakes, to miss an opportunity and to grab one. This is the human experience, and none are weaknesses real or perceived.

But, if you actually have a weakness — something that legitimately hurts others and yourself — don’t approach it from a posture of shame. Approach it from a posture of vulnerability, that you know you’re weak, and that you need help.

WHOLENESS ISN’T …

Wholeness isn’t happiness. You are a whole human when you’re happy. You’re whole when you’re sad. You’re even whole when you’re broken. Because …

Wholeness isn’t the lack of brokenness. We’re not like inanimate objects, like plates, or cars, or clothing. If an inanimate object is broken, it doesn’t have the same usefulness that it did when it was whole. No, humans are the opposite. We become more useful, more powerful, more whole the more we lean into our brokenness.

Wholeness isn’t the only way you can be lovable. The idea that broken things can’t be loved is simply untrue, but the ever pervasive narrative that’s perpetuated through Hollywood and everywhere else is that only perfect things can be loved. Here’s the truth: perfect things are broken and we can be loved.

*****

This is the truth: Death, grief, tears, brokenness, weakness (perceived or real) doesn’t move us farther away from our humanity, it can move us closer. It’s not a question of “are you less of a person when your grieving?” The question is: can you approach your grief without shame, accept the process, and embrace the new normal?

I write in my book:

“I believe there’s a place hidden inside humans that hasn’t been wounded by shame and fear. A place where there’s still innocence, where we haven’t been calloused by the friction of hurt. A place so innocent that we can be ourselves, in all our messiness and peculiarity, and still believe that we’ll be loved. It’s a place where there’s no need to put up fronts of perfection and wholeness, no need to paint our faces and cover our flaws. That place is often exposed by death. We picture death’s hand as cold, capricious bone when it may be the hand of an expert clockmaker, able to turn and fix those intricate parts that still harbor a sense of Eden, where vulnerability is normal, and shame has little power. At Chad’s funeral, Eden had been rediscovered. No one was looking at their cell phones. No one was preoccupied with what they had done that morning or what they had to do afterward. IN onebeautiful moment, everyone was present and shame free.

*****

If you like my writing, consider buying my 2017 Nautilus Book Award Gold Winner, Confession of a Funeral Director (click the image to go to the Amazon page):

10 Ways Working in Death Care Affects Me as a Parent

Bad Table Manner Teacher

Bad Table Manner Teacher

It was passed down to me by my father, and down to him from his father. When you work with death, you talk about death, even around dinner. That’s all fine and good if it stays in-house, but when Jeremiah goes on his first date and starts rattling off what his dad does for a living, it might hurt his chances for a second date.

More Cautious

“Remember to wear your bicycle helmet because I buried a kid that didn’t!”

“No, that seat belt needs to be across your chest. I don’t want you to be launched through the windshield like Billy Johnson.”

“There’s a reason I want you to chew your food. Because if you’re ever eating alone and you choke, well ….”

“Never underestimate the power of an angry beaver.”

It’s easier to switch off work

You think it’d be the opposite. I mean, going from wrestling a dead body onto an embalming table to wrestling your son an hour later is a little outside the norm.. For me, being around death helps me value every moment I get with Jeremiah. Death makes me love his life.

Funeral Suits. The children of funeral directors have funeral suits.

Because we’re not afraid to send our kids to funerals. And we also want them to look sharp doing it.

Dead Bodies are No Big Thing

I don’t remember the first time I saw a dead body, and neither will Jeremiah … because they’ve just been a natural part of our lives since as long as we can remember.

Dead Children are a Bigger Thing

Any death care worker has seen their share of the unspeakable. It affects all of us. Whenever we have to serve a family that lost a child, everyone at the funeral home is moody, on edge and generally not pleasant. It’s hard enough as is, but when you see YOUR child in the face of the little one in your prep room, it drives it home even deeper. This is the stuff of literal nightmares.

LOVE YOUR ELDERS

It’s probably because I model it to him. If you work in the funeral business, you naturally work with people who are older. As kids, we’re taught to respect your elders. As we age, that respect turns to love because the older they come, the better they are (for the most part). Jeremiah sees my love (and respect) for the elderly and he mimics it. I love that.

Spoiler Spoiler

If I’ve seen a movie or show before someone else, I usually make the spoiler joke that “everyone dies at the end” because I’m a funeral director it’s a nice double entendre. But, in Infinity Wars, that joke is only half true. Whoops. Sorry.

Don’t you hate spoilers? Working in the funeral business is one big spoiler because the dead love to remind you about the ending of your story.

Enter children with all their life, all their hope, trust, and carefree resilience. All that, all that they are, has a way of spoiling the power of the spoiler. Because some narratives are so good, you can thoroughly enjoy the story even when you know how it ends.

Missing Events

Like every parent, we try our best to be at their sports games and stuff happens. When we’re on call, nothing is sacred, including time with the kids.

Pursue your dreams, kid and I’ll celebrate your every step.

We’ve all been hammered with these little truisms like, “live so you don’t have regrets on your deathbed”, and “live like you’re dying”, and, #YOLO. For those of us who are close to death, truisms have been hammered home much deeper.

Often, though, we use those truisms for ourselves, and our dreams, and our careers, but the profound thing that death has taught me is that the best life I can live is when I’m celebrating someone else. That someone else, for me, is Jeremiah.

*****

If you like my writing, consider buying my 2017 Nautilus Book Award Gold Winner, Confession of a Funeral Director (click the image to go to the Amazon page):

What It’s Like Embalming a Child Killed by Gun Violence

Another school shooting. Ten people died, nine students. This is the 22nd school shooting since the beginning of 2018. The 22nd in just over five months. Let that sink in.

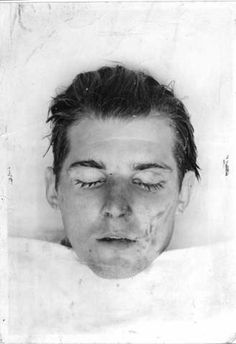

At this point, we’re tired of it, tired of it happening, tired of hearing about it, and tired of the polemics. So maybe a perspective from a funeral director and embalmer can help scratch off the callous. As a forewarning, the content in this post will be disturbing as I present the problems embalmers face with gun wounds.

I was told in funeral school that funeral directors should never, under any circumstances, divulge their political opinions. “Unless you want to lose business,” my prof told us during the fall of 2004 when the Kerry Vs. Bush political battles were headlining, “keep your politics out of death care. Death is about unity, goodwill, and grace. Politics is the exact opposite.”

My prof was right on both accounts. I write in my book how death allows us to transcend our little groups and see the bigger picture, namely that at our core, we may be Democrat or Republican, black or white, gay or straight, but we’re also fundamentally human. Our distinctives are important and should never be minimized, but death gives us a little reprieve from the unneeded tension because it allows us to focus on the things that bind us together, not the things that divide us. Remember 9/11? Remember how we joined together for a month or so, united?

There’s a time for political action, and as I’ve argued before … if grief is the basis for someone’s action, it’s not our job to lecture that activist because — although death can be a classroom — you are NEVER the teacher. Simply: our job as outsiders is to give the grieving a refuge, not put them in a classroom.

While funeral directors rarely get political, that doesn’t mean we don’t get involved. Seventy-one-year-old Ronald Jones, a funeral director from St. Louis was tired of burying kids killed by gun violence, so he finds at-risk youth on the streets and mentors them.

This from an interview with Mr. Jones, a piece that captures what funeral directors experience when a death is by gun violence and the family wants some restoration:

Many times Jones said he’s recognized people that he’s cared about come across his (prep room) table. Nearly seven years ago, he lost someone that he had mentored for years. To this day, Jones still refers to her as one of his “kids.” She was shot 11 times. The bullet wounds left her face mutilated and her skull shattered. When he saw her, Jones didn’t even recognize her.

It took him a few days just to sew up all of the entrance and exit wounds to her face, and he had to use 254 pieces of wire to reconstruct her skull. But as he got closer to making her whole again, things started to become a lot clearer.“When I pulled the face over the skull, I almost fell out on the floor, because I’m recognizing somebody that I know and was dear to me,” Jones said. “So I was mandated to really do my best to bring her back so her baby and aunt who raised her could bring some closure.”

Even though funeral directors are rarely political, we often see the outcome of violence, on both a physical and psychological level. We put together faces, and we attempt to put together the funerals for those faces. Seeing that, touching that, stitching that back together … it does something to a person. I can’t exactly say what it does except that it makes the world’s problems seem so much larger and so much more difficult.

What is it like putting faces back together? Well, it depends.

Either today or tomorrow, the parents and the families of the Santa Fe shooting victims have to make this decision: do we want to have a public viewing for our daughter/son’s body, or not?

As the details of the shooting were coming out, I was particularly struck by the fact that the Santa Fe High School shooter used a handgun and a shotgun. From a number of accounts, it seems the shotgun was his weapon of choice. If so — like an assault rifle as well — a shotgun can create a variety of difficulties for an embalmer trying to restore the child.

If I’m a parent, and a public viewing with embalming/restoration is something I want, I’m hoping that my child was one of the ones killed by a handgun (the shooter used a .38 revolver).

I’ve buried a number of people who died from both shotgun wounds and handgun wounds, and there are three general categories of possibilities for a death by firearm, and some different embalming methods we’d likely have to use for each. One or more of these methods would need to be employed for any child shot in a school shooting:

One: SHOT TO THE HEAD: A handgun will have a small entry point and a slightly larger exit point (assuming it exits the body). A person can shoot themselves point blank in the skull and most of the time, the entry point is a little smaller than a penny. That’s usually a simple job for us to fix. Some basic cosmetology and you can hardly tell where the bullet entered.

A shotgun is completely different. Depending on how close the shooter is to their target, a shotgun spray can disfigure a person’s body, especially the face.

Assuming the family wants to see the body, funeral directors have to be honest with ourselves, “Can we reconstruct the severe trauma? Can we make this look somewhat normal?” If the facial features have been ripped off, usually the answer is “no.”

If the shot was to the back of the head, the skull is likely fragmented, but as long as the spray didn’t exit through the front of the face, we can piece the skull back together, or reconstruct the skull through a variety of options.

Two: BODY SHOT: No biggie. A body shot might damage the arterial system, but it’s unlikely that it’d do any more damage than an autopsy, which is something embalmers encounter on a regular basis. In fact, many states require a full autopsy for any suspected homicide, which would mean the heart — the center for arterial distribution of the embalming fluid — would likely be removed for examination. Multi-point injections are a rather regular occurrence for embalmers. A body shot is the best case scenario if the family wants their child to have a public viewing.

Three: MULTIPLE SHOTS TO HEAD AND BODY: If the head and body have sustained multiple shots, the embalming process is much more complex as we have to raise injection sites on the body for specific locations. In Sandy Hook and Parkland, Flordia, the shooters used assault rifles, which resulted in many of the victims being shot numerous times with higher velocity bullets. Multiple shots from an assault rifle, depending on where they hit and what caliber bullet can cause significant trauma to the head and body, making embalming and restoration much more technical, if not impossible.

If the parents want their child embalmed for a viewing, it falls on us to do our best, and be honest with the family if it’s an impossibility. Some embalmers will be putting countless hours into restoration to make the Santa Fe children look as much like they did before they got shot at their school.

And when all is said and done, the best job they can do might still not be perfect. But this is violence, this is a tragedy and perfect disappeared as soon as the shooter starting pulling the trigger.

At this point, most articles about school shootings end with an action point or a political sound byte. I’m a funeral director and embalmer. I’m not supposed to get political. I can’t tell you how to fix the problem, all I can say is that I wish we never had to fix the fractured faces and bodies of school children. I wish we never had to hear mothers and father weep. I wish we never had to … but we do.

*****

If you like my writing, consider buying my 2017 Nautilus Book Award Gold Winner, Confession of a Funeral Director (click the image to go to the Amazon page):

10 Things about Funeral Director’s Love Lives

I know what you’re thinking. “Caleb, you’re reaching on this one. You’re just looking to write a post that lets you pluck the low hanging jokes, like ‘Funeral directors can make you stiff’, etc.” You got me there. I tend to pick the easy jokes, but bear with me because this is a thing, a thing that NOBODY TALKS ABOUT.

Because when you work in a profession that sees nearly 80% of their workforce burn out before they hit the five-year mark of employment, you can bet that their love lives are a little different than most.

One. Commitment confusion.

This job asks us to marry it. It asks for us in sickness and in health, night and day, in good times and bad. Death is always asking, always needy, always calling and texting. It’s tempting too, because when we can fulfill the needs of death, it can create a kind of co-dependent relationship where we fulfill the needs of death and death fulfills our needs of feeling important. When death is so demanding, all other relationships become mistresses.

Two. Good back rubs.

It’s very true. We give very good backrubs. And the fact that we give good backrubs has nothing to do with the fact that we’re constantly massaging the dead to make sure the embalming fluid get’s evenly distributed throughout the decedent’s corpse.

Three. Bi-polar Sex Drive.

The Jekyll and Hyde Syndrome also affects our physical relationships with our partners. This is real. And surprisingly, the show Six Feet Under captured this well in the complexity of their characters. For all of us, our sex drive can be seemingly unpredictable. For those who work around trauma, death, and grief, those drives seem to go to utter extremes. Because sex — for some — is a natural stress diffuser, and when we’re under professional stress on a constant basis, our desire for that physical relief can — at times — be overwhelmingly strong. Other times, that stress is so overwhelming we don’t even want to be touched.

Four. General Audio Illusions

Funeral Director Dude (while having sex): Oh, Laurel! I love you so much!

Laurel: WHO THE HELL IS ‘YANNY?!’

I suppose we all suffer from that problem.

Five. On Children

After a bad day at work: “I don’t think we should have children. This world is too dark and scary.”

After a good day at work: “WE SHOULD HAVE CHILDREN RIGHT NOW!!!”

Six. Transference

Transference is a psychological term that funeral directors have some practical experience dealing with. Some people we deal with have major problems and baggage that gets fanned to flame by grief and bereavement. Often times, they take their problems, their anger, their frustration and instead of dealing with their grief and bereavement, they take it out on us. If you’ve been in the business long enough, you know not to take it personally, but it’s nonetheless difficult to take a capricious verbal lashing for no apparent reason other than transference.

But here’s how it affects relationships: funeral directors too often do the same, especially to their significant others. See, generally, we take out our problems on those we see as our equals or those we see as inferior. While I hope nobody is in a relationship with someone who views them as inferior, most of us tend to be in relationships with people we perceive as equals. So that stress, baggage, angst that we pick up in the funeral business often gets taken out on those closest to us in our personal lives.

Seven. Bringing our Work Home

Most jobs can be left at work. But there’s so much personal stuff with the funeral business, so much stuff that affects US, that it’s almost impossible to leave things there. It also doesn’t help that there are still many family-run funeral homes that literally have their home on the second floor of the funeral home. Work is literally one flight of steps away from everything.

Eight. Flowers.

We’ll always give you flowers. Endless flowers. Forever. Mind you, they’re likely left over funeral flowers, but still.

Nine. The Chaotic Schedule

If funeral directors are going to have love lives at all, there has to be an understanding: when we’re on call, nothing is safe and nothing is sacred. We could be at a fancy dinner and our phone rings and we have to go. Watching Netflix, phone rings and we have to go. Sex, phone rings, go quickly then go.

Ten. The Jekyll and Hyde Syndrome.

Okay. I’m making this syndrome up. Nevertheless, it describes how the funeral business makes you feel. Here’s a brief 10-day snapshot of how quickly certain deaths and certain funerals can change us:

DAY 1: We come home from the funeral home and we’re serious and philosophical, contemplating the meaning of life. “Babe, I think we need to pursue our dreams and hug each other more often BECAUSE WE ONLY GOT ONE LIFE!”

DAY 2: The next day, we come home after having dealt with some tragic death and we’re like, “Babe, life’s meaningless … maybe we should just get drunk every night.”

DAY 3: “Lovie, I think we need to up our commitment to God and the church because this family I served today … there’s so much good in faith!”

DAY 4: After a bad experience with a pastor, “Lovie, let me tell you: religion is horrible. These people. Ugh. So. Much. Fake.”

DAY 5: We want to tell you everything, from the removal to the embalming, to the sights and the sounds. We chatterbox on and on for hours about our day.

DAY 6: “Snuggie Woogems, I DON’T WANT TO TALK. JUST LEAVE ME ALONE.”

DAY 7: “Jelly Bean, I think we should be saving more for retirement ’cause I met with this older couple who have nothing.”

DAY 8: After getting a death call for a young person: “Jelly Bean, let’s spend it all. What makes you happy? Shoes? Let’s buy all the shoes … because we could die tomorrow.”

DAY 9: “I’m on a diet today, Chipmunk. I want to age as best as I can. Quality of life, Chipmunk. Quality of life. Also, we need to join the gym.”

DAY 10: *Stress eats an entire pizza and sleeps for 14 hours*

DAY 11: “I know my job’s hard, Love Muffin, but at least we have an income.”

DAY 12: After a 12 hour day on what was supposed to be a day off, “I’m quitting, Love Muffin. Time to downsize.”

One day, we’re one person and the next day we’re a completely different person because when you attend to the dead and their funerals on a daily basis, the lives of the people you serve tend to change you, shape you, challenge, stretch, anger, encourage and confuse you all at once, all the while confusing your partner to no end. You just have to hope your partner loves your chaos.

*****

If you like my writing, consider buying my 2017 Nautilus Book Award Gold Winner, Confession of a Funeral Director (click the image to go to the Amazon page):